Numerous small businesses in the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area serve delicious ice cream.

Numerous small businesses in the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area serve delicious ice cream.

150 years ago, on July 15, 1874, the conflict over water availability in the Cache la Poudre River Valley erupted. But where did the conflict begin, and why was the river so contentious? Let’s step back in time and find out…

People have been using the water in the Poudre for far longer than 150 years. The Arapaho, Ute, and Cheyenne peoples, along with others, and their ancestors, lived beside and used the Poudre for thousands of years before Euro-American settlement. However, around 150 years ago the way humans used this river, and its water, drastically changed.

While Colorado was not among the first areas to see settlement, by the late 1850s-1860s, the region saw rapid transformation. Spurred in part by the discovery of gold in Colorado in 1859, many people from eastern states like Illinois, Ohio, Missouri, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee moved to Colorado. While some tried to strike it rich, the majority were farmers, feeding the steady market for hay, grains, and fresh produce. Moving from states with significant rainfall (on average 45 inches of precipitation) they initially struggled with Colorado’s dry climate (average precipitation of about 15 inches), before realizing irrigation was the key to success—beginning small scale irrigation ditch building efforts in the 1860s.*

In 1870, 144 families traveled westward on the railroad to create an agricultural community called Union Colony (now Greeley). In need of water, the settlers quickly constructed two working irrigation ditches.

The Greeley Number 3 supplied water to kitchens, gardens, and backyards. The Greeley Number 2 to water farmers’ crops. (The Number 1 was never constructed). Union Colony flourished drawing more settlers to the Poudre region. Two years later, Agricultural Colony (now Fort Collins), was firmly established upriver.

In an already dry and arid region, the drought in July 1874 brought a grave threat to the people of Union Colony. Reliant on the Poudre River for water to irrigate their crops and gardens, and to meet community needs, farmers woke up one morning to find the Poudre bone dry at the Greeley Number 3 irrigation ditch headgate.** But what had caused their water supply to completely disappear?

It was discovered that their upstream neighbors at Agricultural Colony and other upstream locations were diverting what little water was available into their own irrigation canals. New upstream irrigation canals, such as the Lake Canal, had the capacity to divert the whole of the Poudre River, and that wasn’t even accounting for the low flow of 1874, a drought year. Capacity had become reality—the newer canals were diverting much of the river’s flow, leaving little for downstream users. Union Colony was outraged, marching to Agricultural Colony with their pitchforks (yes, this really happened) to demand their water back.

To avoid an all-out war, some forty irrigators met at the Eaton schoolhouse on July 15, 1874, to find a solution. “The evening was hot, the structure was small, and the Greeleyites (among them several Civil War veterans) arrived with their guns” (Hobbs & Welsh, 2020).

Fortunately, guns stayed in their holsters and no punches (or pitchforks) were thrown. The injection of Nathan Meeker, Union Colony founder, warned that failure to reach an agreement river water usage could open the floor to allow “a heavy capitalist or corporation” to build ” a huge canal from the Poudre above La Porte [upstream of both colonies] and run it [all the river’s waters] through the Box Elder country” (Hobbs & Welsh, 2020).

Afraid of this outcome, the group laid down their pitchforks and eventually, after many more hours of loud disagreement, came to a compromise. This compromise became the basis of what is known as Western Water Law and the notion of “First in Time, First in Right,” or prior appropriation, still used across Colorado today. Prior appropriation means each irrigation diversion has a priority number—based upon the date they were built and first began to divert (kind of like take a number and get in line). The senior priority users get first use of the water and down the line. However, they can only divert as much water as they hold shares to and must put it to “beneficial use.”

The water provisions established 150 years ago, here in the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area, were eventually written into Colorado’s Constitution and are still in effect today.

This conflict over Western water law not only led to the development of Western water law, but it’s the reason the Cache la Poudre River was designated by Congress as a National Heritage Area.

Learn more at Water War and Law | Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area (poudreheritage.org).

*Irrigation Ditch: Ditches are man-made channels built to store and divert water to where it can be used by farmers to water crops and provide water to towns.

**Headgate: A headgate is an irrigation structure used to regulate the flow of water from a river into an irrigation ditch. Headgates can be opened or closed to control the amount of water allowed through.

Hobbs, G., & Welsh, M. E. (2020). Confluence: The Story of Greeley Water. Jordan Designs.

Image 1 Photo Credit: [1971.20.0004] City of Greeley Museums

Image 2 Photo Credit: Archive at Fort Collins Museum of Discovery. [H07772]

Image 3 Photo Credit: [AI-2526] City of Greeley Museums

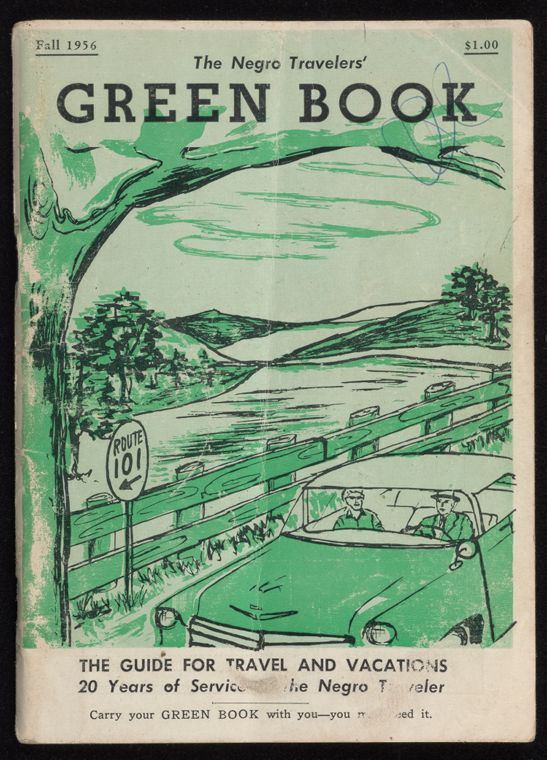

Carry your Green Book with you….you may need it.

With summer comes the travel bug, and millions of Americans hit the road in search of adventure. While we check to make sure we’ve got our snacks and charged phones, we take for granted that we’ll be safe and served at the place we chose to fuel up, eat up, or rest up. Not long ago, however, safety and service while traveling were not expected by large numbers of Americans. Read on to discover how one Greeley woman was part of an effort to change that. . .

As car ownership exploded across the United States during the 1920s, a road trip became a new reality for thousands of Americans. But the lure of the open road was also filled with risk for African American travelers. Jim Crow laws, segregation policies, and racist “white only” traditions meant Black travelers couldn’t assume a town had a safe place to eat or sleep. “Sundown Towns,” across the country, and as close as Loveland, banned African Americans in city limits after nightfall, often removing them by force, adding to the risk of a car breakdown. Without knowing where they could safely stop, many African Americans were hesitant to embark on a road trip.

In 1936, a Black postal carrier from New York, Victor Green, came up with a solution—the Negro Motorists Green Book. Part travel guide, part survival guide, the annual guidebook helped African Americans navigate a segregated country for 30 years. Beginning with lodging options, the book soon grew to include amenities like gas, restaurants, beauty parlors, entertainment, golf courses, shops, national parks, and other places welcoming of African Americans. In communities with no known Black-friendly hotels, the book often listed addresses of private homeowners willing to rent rooms to African American travelers. While making safe travel accessible to thousands of Americans, the Green Book also supported Black-owned businesses and transformed travel from survival to a vacation.

For tourists planning a trip to Colorado, perhaps to visit Rocky Mountain National Park (noted in the Green Book as welcoming), the guide suggested lodging options across the state. One of which was within the current Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area, in Greeley, at the home of Mrs. Eva Alexander.

For 28 years Eva Alexander hosted Black tourists in Northern Colorado. What might Green Book travelers have learned about Mrs. Eva Mae Alexander over a cup of coffee at her table?

Perhaps they would have learned of her Texas childhood, where her parents, Ervin and Mary Cruter, lived and worked in the home of a white doctor as cook and hostler (cared for horses). Would she have mentioned that at eight she was already working as a servant, or would she have instead shared memories of playing with her little brother? Maybe she would have shared that the family moved to Trinidad, Colorado around 1905. How her father got a job as a railroad porter, and she and her mother no longer had to work. What stories would she have shared with Colorado tourists of the southern edge of our state? Did she pass on travel tips or connections?

Perhaps travelers would have coaxed out of Eva that in Trinidad she developed a talent for music, quickly becoming the boast of the town. A traveler from Kansas might have discovered that Eva once lived right around their corner if she shared how, around 1908, she boarded a train and headed to Quindaro, Kansas (edge of Kansas City) to study at the acclaimed Western University. Established in 1865, Western was the earliest Black University west of the Mississippi, and by the 1900s acclaimed for its music school. Did Eva’s home in Greeley have a piano? Perhaps, if it did, travelers might have convinced her to play.

A photograph of a handsome, young man in Eva’s home might have unlocked for guests the story of George Alexander, a vibrant student at Western who caught Eva’s eye. Though she took a job in Washington D.C. to teach music after graduation, she didn’t stay long. By August of 1913 she had returned to Kansas to marry George. The son of a prominent minister and graduate of Western University’s tailoring school, George had quickly worked his way into management of a white owned tailor shop, but also owned and managed his own tailoring and dry-cleaning store for Black residents. The African American newspaper, the Western Christian Recorder (incidentally still the oldest continuously published African American paper in the U.S.), joyously announced the marriage, being sure to mention Eva was an accomplished musician. Eva soon set up her own business, a music studio. Two years later, their daughter, Olivia, was born, followed by William. Eva might have smiled recounting the story, her family was now complete.

But then, Eva’s face might have saddened. With deep connections to the African Methodist Episcopal Church, George had become a minister and the young family had moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1917. Six months later, George suddenly died of pneumonia, leaving Eva, “a lone widow, struggling with two small children for an honest livelihood,” as she would later write. With two children under four, Eva moved to Globe, Arizona, taking a job as a teacher at a segregated public school. With her guests would she have shared her experience, or perspective on the ongoing discussions of school segregation or the Civil Rights movement?

With their coffee long gone Eva’s guests might have asked, “How did you end up in Greeley?” Maybe Eva would have told them what we, historians, don’t know—what inspired her to move two young children to a Colorado town she’d never lived in—packing up Olivia and William in 1922 and moving to Greeley, where she purchased her home—the Green Book stop—at 106 E 12th Street.

The rest of Eva’s life travelers might have been able to observe for themselves. Her deep involvement in her local church. Her care of her elderly neighbor, Rev. W.H. Mance, who appeared alongside Eva in the Green Book as a host for travelers until his death in 1943. Her caring nature which led her to pursue careers as a housekeeper, nurse, and later volunteer for homebound seniors. Her generous spirit that opened a home to tourists from 1939-1967—the entire run of the Green Book outside of New York. Her strength to raise two children as a single mother, and the pride she must have felt in their success. Olivia went on to lead the HeadStart program in Phoenix where she lived with her husband and daughter. William pursued a career in film—creating newsreels on African American soldiers during WWII, then establishing his own company in New York and London, producing films and later documentaries that went on to win UN awards. He was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame.

What stories would a guest in Eva’s home have departed with? Heading out, guided by the Green Book and a hope in a more equitable future where tourists to Colorado’s mountains, cities, and parks would be welcomed for a night in any hotel, regardless of race.

In 1948 the authors of the Green Book wrote, “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. . . It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication, for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.” In 1964 the Civil Rights Act banned racial segregation in restaurants, hotels, and public places. Three years later, in 1967, the final Green Book was distributed. Mrs. Eva Alexander was in the final issue.

Eva Alexander died in 1987, she was 95 years old, and is buried in Sunset Memorial Gardens in Greeley. Her home still stands in Greeley.

“Alexander-Cruter Nuptials.” Western Christian Recorder. 8 August 1913, p1.

“Another Progressive Young Man.” Western Christian Recorder, 10 October 1912, p1.

“Bill Alexander Working on Film in Sierra Leone.” Greeley Daily Tribune, 2 May 1961, p.6.

“Globe—Miami.” Phoenix Tribune. 3 April 1920, p.4.

“Globe—Miami.” Phoenix Tribune. 27 May 1922, p.2.

“Mrs. Eva Alexander Marks 80th Birthday.” Greeley Daily Tribune, 8 September 1972, p.17.

“Mrs. Eva Alexander spends years doing volunteer work for residents.” Greeley Daily Tribune, 20 December 1976, p29.

“Notice! Notice! Notice!” Western Christian Recorder. 1 January 1914, p2.

“Rev. G. G. Alexander.” Albuquerque Journal, 10 February 1918, p3.

“Trinidad News.” Franklin’s Paper the Statesman. 27 July 1912, p1.

United States Census Records from 1900, 1930, 1940, 1950. Accessed on ancestry.com

U.S. City Directory Records, Trinidad, Colorado. 1909 and 1912. Accessed on ancestry.com

Victor H. Green & Co. The Negro Motorist Green Book collection. New York Public Library Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division. New York, NY. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book#/?tab=navigation