By Heidi Fuhrman, Heritage Interpreter

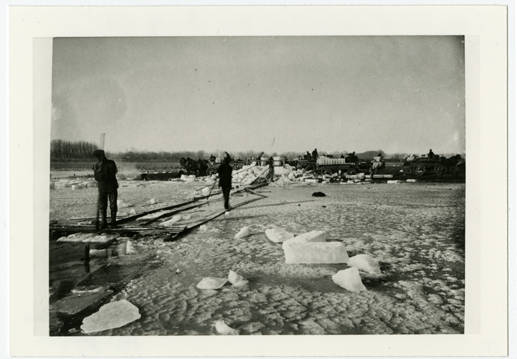

”The ice harvest commenced this week in Fort Collins. Giddings is cutting in the river just northeast of town and finds the ice about one foot thick and of fine quality.

Fort Collins Express, December 31, 1887

When you think of historic industry along the Poudre you might envision farm fields stretching across the horizon, or the towering smokestacks of the Sugar Beet factories in Fort Collins, Windsor, and Greeley, turning beets into white sugar during the early 1900s. While you may know the water of the Poudre past was key to ag industries, you may not realize that the water supported another key industry—ice.

Today, ice is a simple reality. It fills bags in gas stations and pours from dispensers, chances are it comes out the front of your refrigerator (or fills a tray in your freezer, unless, like me, you prefer to save that space for ice cream). In modern Colorado ice isn’t even considered a luxury, it just is.

In the decades before electric refrigeration, however, ice was a key ingredient of food storage and safety. The “icebox,” an early form of refrigerator, was invented in 1802, and by the end of the 1800s nearly every home in America had this early “appliance.” Unlike your modern refrigerator which uses electricity, an ice box, to maintain a cool temperature, required … well … ice (a continuous supply).

Imagine a world where a freezer doesn’t exist. Three seasons of the year, it’s impossible to create the ice your ice box relies on. This means a year’s supply of ice blocks must be harvested in one season—winter— when it naturally forms on bodies of water.

”Several wagon loads of saw dust went through here last week, headed for Windsor. That means the Windsor farmers are getting ready to put up ice, for this is the month of the ice harvest. Ice hands seem to be scarce at $2,50 per day.

Larimer County Independent, January 6, 1904

You may be more familiar with the process of ice harvesting than you realize. Have you ever seen Disney’s movie “Frozen”? The opening scene depicts a historically accurate ice harvest! (Go on, look it up now, I’ll wait). Here along the Poudre, ice was usually harvested in January or February when ice on the river and reservoirs was thickest, historically from 10-15 inches.

Ice harvests on the Poudre River began as early as the 1870s, when communities like Greeley and Fort Collins were established. In the 1800s it was more common for farmers to cut their own supply. The ice harvest was often a community event, requiring multiple men to man the ice plows, saws, pikes, and tongs required in a harvesting operation. Most farms had their own ice houses where large blocks of ice were stored between layers of sawdust or hay to keep melting at minimum.

While farmers continued to cut their own ice for many decades, a few ice storage and distribution companies did form, including J.F. Vandewark’s in Fort Collins and Windsor Lake Supply company in Windsor. These companies often hired local men, a way for farmers to make extra cash during the quieter winter months. These companies, which also often sold and delivered hay and coal, had large ice houses located in the downtown district. Throughout the year, they would cut large blocks in storage into smaller 25–100-pound blocks that were distributed by ice wagon to local homes. Each ice block would generally last 1-4 days, depending on the outside temperature. Homeowners would indicate they needed a new block by placing an ice sign in their window with the appropriate number of pounds needed at the top.

“J.F. Vandewark finished up his ice harvest in good time and now has over 2,000 tons of the crystals stored away for next summer’s use.” Feb 13, 1907

Windsor is unique in that the larger portion of the ice harvested off Windsor Lake (then Lake Hollister) was shipped to Denver. As early as 1883, Windsor Lake Supply Company were filling 1,000-ton contracts. This ice was cut and shipped to Denver where it was sold to cool train shipments during warmer months. In the 1890s, this industry had grown so large that the Union Pacific Railroad added a track near the edge of the lake to simplify loading. A portion of ice was also stored at the Windsor icehouse which sat adjacent to the edge of Windsor Lake.

This industry, as you might imagine, was heavily weather dependent. Warmer than expected Januarys could, and did, ruin ice harvests, most notably in 1906.

Ice harvests were reported in every community down the Poudre from Laporte to Greeley for decades. The last reported ice harvests were conducted in the 1930s as the electric refrigerator replaced the ice box in local homes.

Vandewark’s “Riverside Ice & Storage Co.” building which sat at 222 Laporte Ave in Fort Collins was deconstructed in the mid-2000s (you can watch a video tour of it here). Windsor’s Ice Storage building is also long gone. However, Greeley’s still stands at 1120 6th Ave and is on the State Register of Historic Places.

Vandewark started his natural ice and transfer business in 1890. It expanded and in 1902 he built an artificial ice plant on Riverside Drive. He sold the site to the Union Pacific Railroad in 1910 and in 1911 built a new plant at 222 Laporte Avenue which he operated as the Riverside Ice & Storage Co., Fort Collins, Colorado. Mr. Vandewark was born in 1870 and died in 1963 at the age of 93.

And the next time you visit Centennial Village in Greeley, the Avery House in Fort Collins, or the Windsor History Museum, keep your eyes open. You might just spot an ice sign in a window or an ice box inside a kitchen or porch. Nods to a bygone era along the Poudre.

![The Riverside Ice and Storage Company and Risco Gas Station, 222 Laporte, Fort Collins, Colorado. "Archive at Fort Collins Museum of Discovery” [H08091]"](https://poudreheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/ph_14745_medium.jpg)