What do we know of the earliest inhabitants of Colorado? What do we know about the early ancestors of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, Apache, Shoshone, Kiowa, and other tribes who called the mountains and Great Plains home; the ones who walked along the Poudre in the ancient past, long before the river was called by that name?

Long ago, Paleoindians called this land home and archaeology helps peel back layers of time to give us a dim glimpse into their lives. Humans have lived and migrated through Northern Colorado for what archaeologists estimate as at least 12,000 years, although some Native American nations hold the belief they have been here for time immemorial. The earliest inhabitants to appear in the archaeological record are called Paleoindians by archaeologists or the “Ancestors” or “Ancient Ones” by many Native Americans, referring to a time period from roughly 12,000-7,000 B.C. For reference, this is long before the cliff dwellers of Mesa Verde in southern Colorado whom we often think of as ancient, but who called Colorado home only 600-700 years ago. Paleoindian sites are often few and scattered, however, there is evidence of these prehistoric peoples throughout northern Colorado and southern Wyoming, including projectile points (e.g. arrowheads), stone tools and later pottery, ancient bison and mammoth bones that show signs of being hunted, remains of camp and dwelling sites, and even burials.

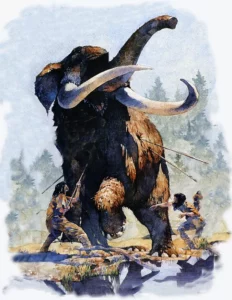

The Paleoindians of the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area region were nomadic, traveling in groups as they hunted mammoth and bison antiquus, a larger ancestor of the modern bison; crafted tools from the landscape or materials from as far away as Texas; and shifted from use of the atlatl, an ancient weapon, to bow and arrow. Archaeologists and anthropologists break ancient history in this region into several stages.

- Clovis 11,500—10,800 BC [Dent Site]

- Folsom 10,800—9,700 BC [Lindenmeier]

- Plano 9,000—6,00B BC

Of the thousands of archaeological sites within Larimer and Weld counties, there are several that date to Paleoindian periods that give us an understanding of how ancient people used the area we call northern Colorado.

Dent Site

A bit beyond the Cache la Poudre River, south of Greeley near Milliken is one of Colorado’s oldest archaeological sites. Discovered in 1932 by a railroad foreman, the Dent Site dates to the Cloves period (remember, that’s the oldest one) and contained mammoth bones showing signs of hunting and butchering along with two Clovis spear points. This site holds valuable evidence for people in Colorado as early as 12,000BC. Many of the artifacts uncovered from the Dent site are part of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science collections. (The public cannot access the Dent Site).

Lindenmeier Site

Today, if you visit the Lindenmeier site you will encounter a landscape not very different from what archaeologists found in the 1930, windswept prairie rising into the foothills of the Rockies, undulating with valleys and bluffs. Although it doesn’t look like much, this archaeological site is one of the most important in the western hemisphere, and forever changed how we understand ancient Paleoindians from the Folsom era—now called Folsom people.

In 1924, local amateur archaeologists Claude C. Coffin, A. Lynn Coffin and C.K. Collins discovered a style of “arrowhead” they had never seen before on William Lindenmeier’s ranch north of Fort Collins. Over the next several years they kept finding this distinctly shaped projectile point (now called Folsom point). In 1927, after the discovery of a similarly shaped projectile point in Folsom, New Mexico, the Coffins reached out to the Smithsonian Institution inviting an archaeologist to visit. The 1920s and 1930s were a time of fierce debate amongst archaeologists as they tried to answer the question, “How long have humans occupied North America?” Some believed humans had not lived on the continent for more than six or seven thousand years, while others believed it to be longer, but had yet to find solid evidence. The discovery of a point in Folsom, NM was the first step to proving a theory of longer human occupation of North America but there were many missing pieces. The Lindenmeier discovery settled the question once and for all.

In 1934 the Smithsonian Institution sent Dr. Frank Roberts to investigate the Lindenmeier ranch. From 1935-1940 Roberts excavated what is now called the Lindenmeier Site, one of the largest and most complex Folsom sites in the Western United States, a site that provided not only proof of early human habitation of North America but also insight into a culture more complex than previously imagined.

The Lindenmeier site is situated along the edge of an old stream valley, buried under 12-15 feet of sediment, silts, and clays deposited by floods and winds over thousands of years. The camp, over 11,000 years old, is large, likely created by multiple occupations over several generations as one or more groups returned year after year to a favorite campsite. Clusters of artifacts help define different areas of the camp—work areas where Folsom people manufactured projectile points, repair areas for tools, cooking areas, spaces where animal hides were cleaned and transformed into clothing and shelter—and offer information on how Folsom people lived.

The Lindenmeier site revealed that Folsom people dwelt in places for long periods, traveled or traded over long distances (raw materials from as far away as Texas were found), created items that were both useful and decorative, cooperated socially, and did more than just hunt. It revealed ancient people did more than just survive; they thrived! Over 51,000 artifacts were discovered, including stone tools, animal bones, remains of hearths, projectile points, bone needles, beads, and paint. Perhaps the most important discovery was a broken Folsom point lodged in the backbone of a bison antiquus (the ancient ancestor of the American Bison) that settled the question if ancient bison and human lived together.

The excavation of the Lindenmeier site pioneered archaeological methods that were new in the 1930s, but have today become common practice, such as taking detailed records of where every object was found which helps archaeologists understand the story of a site. Artifacts from Lindenmeier are held at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, and the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery. You can visit both the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery to see artifacts found at Lindenmeier and the site itself, which is now part of Soapstone Natural Area. Read the “Explore!” section below for more info.

Jurgens Site

Dating from the Plano period (9,000-6,000BC), the Jurgens archaeological site is about nine miles east of Greeley near the South Platte River. This archaeological site contains evidence for a long-term camp, a short-term camp, and a processing area where game was butchered after a hunt. Remains of at least sixty-eight bison and several other small animals along with tools were discovered at this site. The Jurgens site revealed information about Plano period people such as the game they hunted, the techniques they used to hunt and process bison (their most important resource), and the way they structured sites for different needs. Because of its importance for helping archaeologists understand how important bison were to the economy of the Plano period, the Jurgens site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. (There is no public access to this site).

After the earliest inhabitants (Paleoindian period) came the Archaic period (6,500B.C.—200AD). There are few archaeological sites from the Archaic period in Colorado, but ones we do know of, show us that Archaic inhabitants of northern Colorado lived lives similar to their Paleoindian ancestors.

Kaplan-Hoover Bison Kill Site

One important Archaic site in Colorado is in Windsor, just a half-mile south of the Poudre River at the base of bluffs, today in a neighborhood. The Kaplan-Hoover Bison Kill site, discovered in 1997 during subdivision construction, is one of the largest Archaic archaeological sites ever found that holds artifacts from a single arroyo bison kill. Arroyos are steep sided gullies formed in semi-arid climates on the sides of bluffs or mountains by fast flowing water. In Windsor, the arroyo at the kill site leads down from bluffs, where bison would graze, to the river where they could access water. It’s unknown if the Archaic people drove the bison off the edge of the arroyo or trapped them in the arroyo from the river, but in about 860 BC more than 200 bison were killed and butchered at this site. Kaplan-Hoover helps archaeologists understand the importance of bison to Archaic culture in the region and the ways ancient people hunted and processed their game. Read the “Explore!” sections below to learn how you can view the site!

We all want to know more about the ancient peoples that called this region home. What were they like? How did they feel about this place? What stories did they tell? Would they recognize this place today? Through archaeology we get only tiny glimpses of the earliest life on the Poudre. We do know that much like the cultures that would follow them, the ancient peoples of the Cache NHA traveled along the Poudre, surviving and thriving on of the plants and animals the river supported, while adapting and creating tools, systems, and communities.

Explore!

Visit Soapstone Prairie Natural Area (45 minutes north of Fort Collins)

Soapstone Prairie offers excellent views of the prairie and foothill ecosystems and miles of trails ranging from ¼ mile to 9 miles. Visitors can take a look at the Lindenmeier archaeological site, a National Historic Landmark, and may spot bison from the Laramie Foothills Conservation Herd, descendants of the Yellowstone herd.

Hours: Open March-November, dawn to dusk. No entry or parking fees.

Note: No dogs are allowed (including in cars). Be prepared for unreliable cell service. Take water and be prepared for weather.

Respect the cultural heritage of Soapstone Prairie. Do not leave marked trails, designed to protect archaeological resources. In the unlikely event that you see an artifact, leave it alone. It is illegal in Colorado to take artifacts, excavate, damage, or destroy any prehistoric or historic resources. Remember, once an object is removed from its context (place), it loses its ability to educate us about the past.

For more information or resources on history, plants, birding, or more visit the Fort Collins Natural Areas Website.

Fort Collins Museum of Discovery

The Fort Collins Museum of Discovery is one of three institutions that hold artifacts from the Lindenmeier site (the others are the Smithsonian Institution and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science). Visit the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery to view the artifacts and learn more about this and other moments from Cache NHA history.

For more information visit the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery website.

Kaplan-Hoover Bison Bone

While this site is on private property, it can be viewed from the Poudre River Trail in Windsor. From the Poudre River Trailhead at 32554 CR 13 in Windsor, head west on the trail for about 2/3 mile for an interpretive wayside for the Kaplan-Hoover Bison Bonebed. Standing at the wayside sign, visitors can look across the Jodee Reservoir to view the site.

References

Burris, Lucy. People of the Poudre: An Ethnohistory of the Cache La Poudre River National Heritage Area, AD 1500-1880. 2006.

Colorado Plains Prehistoric Context. History Colorado.

Colorado Mountains Prehistoric Context. History Colorado.

“Dent Site.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

“Jergens Archaeological Site.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

“Kaplan-Hoover Bison Kill Site.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

Martin, Brenda et al. Excavation of Lindenmeier: A Folsom Site Uncovered 1934-1940. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, 2009.

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form. Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca.11,500-7,500.

“Paleo-Indian Period.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.