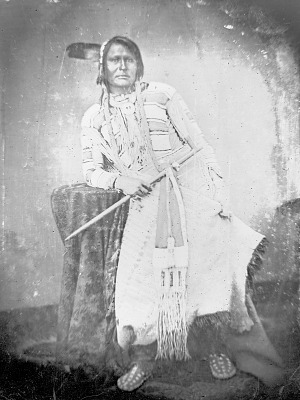

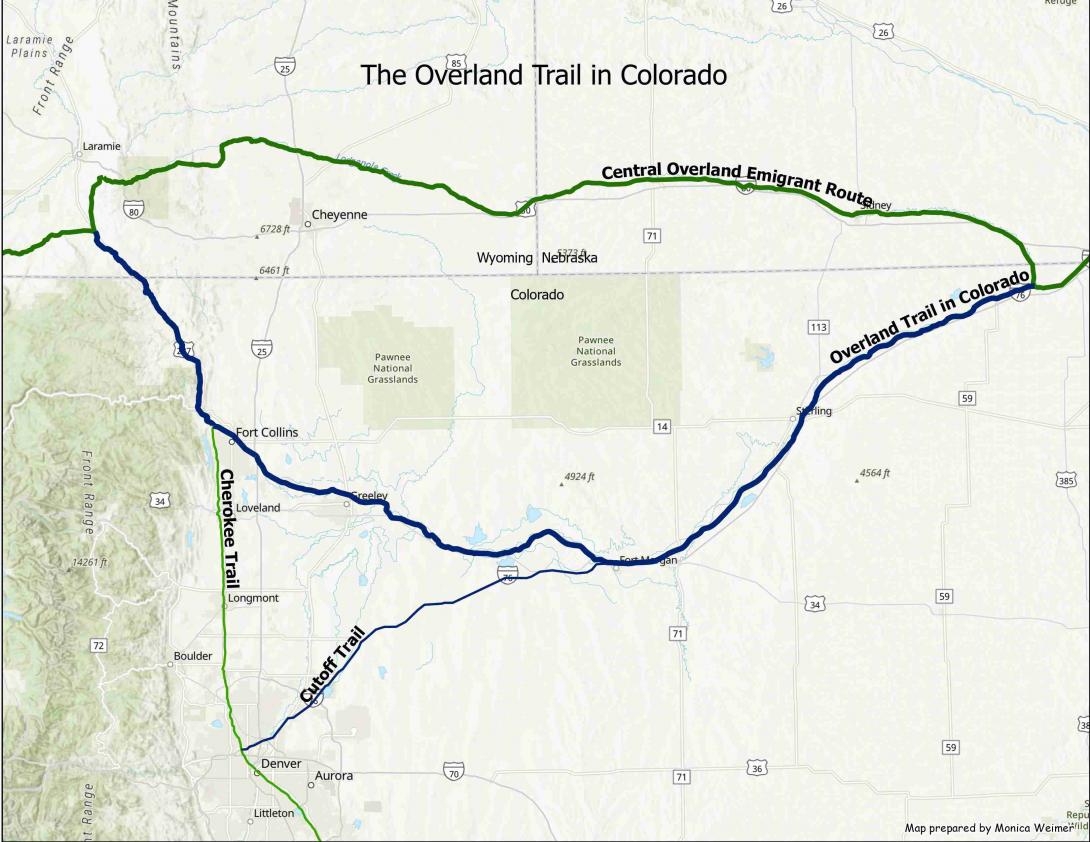

As the land along the Poudre began to fill up with squatters, Chief Friday’s band and a few others remained in their homeland, established friendly relationships with the new neighbors while also advocating for a reservation for the Northern Arapaho along the Cache la Poudre—land they had been guaranteed in 1851 and not signed away. Indian Agent Simeon Whiteley, however, considered the Northern Arapaho’s proposition unacceptable as the land they requested for their reservation bordered the Overland Trail and contained sixteen squatter families who were already building homes and farms (he conveniently ignored the fact that these families were technically illegally occupying the land). The territorial government of Colorado rejected Friday’s request.

By 1864, with many settlers filling the Front Range, Governor Evans needed to create a situation that would lead to the end of Native American claims to lands within Colorado. His following decisions lead directly to the Sand Creek Massacre in November of 1864 in which a peaceful camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho were attacked and over 200 women, children, and elderly were killed. In response to this massacre, conflict between Native Americans and Euro-Americans increased throughout Colorado and Wyoming (the division point of the Overland Trail, Julesburg, was destroyed). “Friendly” Cheyenne and Arapaho bands were ordered to military camps to protect them from government reprisals against “hostile” groups. Still advocating for a reservation, Friday and his band complied, moving to the camp in Laporte. The Northern Arapaho maintained peaceful relationships with the settlers in the Poudre region, even as their land was lost. By 1869, Friday’s band had joined the other Northern Arapaho in Wyoming, giving up hope for a reservation on the Poudre. Left without a reservation of their own, the Northern Arapaho were permitted by the Shoshone to dwell at their reservation, Wind River, in Wyoming. In 1878, Wind River became the Northern Arapaho’s permanent reservation alongside the Shoshone. In less than forty years, less than a generation, tribes across the west had lost their homelands.

![Drawing of Fort Laramie, c1862. Fort Laramie, founded in the 1830s, was a significant trading and Army post located at confluence of Laramie and North Platte Rivers in eastern Wyoming. The fort is now a National Historic Site. Denver Public Library Special Collections, [C63-7ART].](https://poudreheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/ES-17.jpg)

![Robert Strauss cabin on the Poudre River, c1935. Robert Strauss was one of the earliest settlers in the area. He died in the 1904 flood. The cabin was burned in the 1990s, but the remains still stand in what is now Arapaho Bend Natural Area. Image courtesy of the Archive at the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, [H01857].](https://poudreheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/ES-8-300x235.jpg)