Humans have been exploring the Cache la Poudre River region for thousands of years, taking note of the waterways, traversable paths through the mountains, and locations of plants and game as they traveled. In fact, for much of history, the area would have been well known by the many groups of people who traveled and dwelt here during different seasons—people like the Ute, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Souix, and others—whose ancestors explored this region as early as 11,000 years ago.

”[The Cache la Poudre is] a very beautiful mountain stream, about one hundred feet wide, flowing with a full swift current over a rocky bed. We halted under the shade of some cottonwoods with which the stream is wooded scatteringly. In the upper part of its course, it runs amid the wild mountain scenery, and, breaking through the Black hills [Laramie Mountains], falls into the Platte, about ten miles below this place.

John Fremont1843

The medicine wheel (also called the Sun Dance Circle or Sacred Hoop) is an ancient symbol used by many Tribes. It signifies Earth’s boundary the knowledge of the universe. The four colors (black, white, yellow, and red) represent concepts such as the four directions, four seasons, elements of nature, aspects and stages of life, and other spiritual and natural concepts. The arrangement of colors and concepts vary among different Nations. Sometimes this symbol is considered a “compass” in reference to the connections to the four directions.

The Spanish

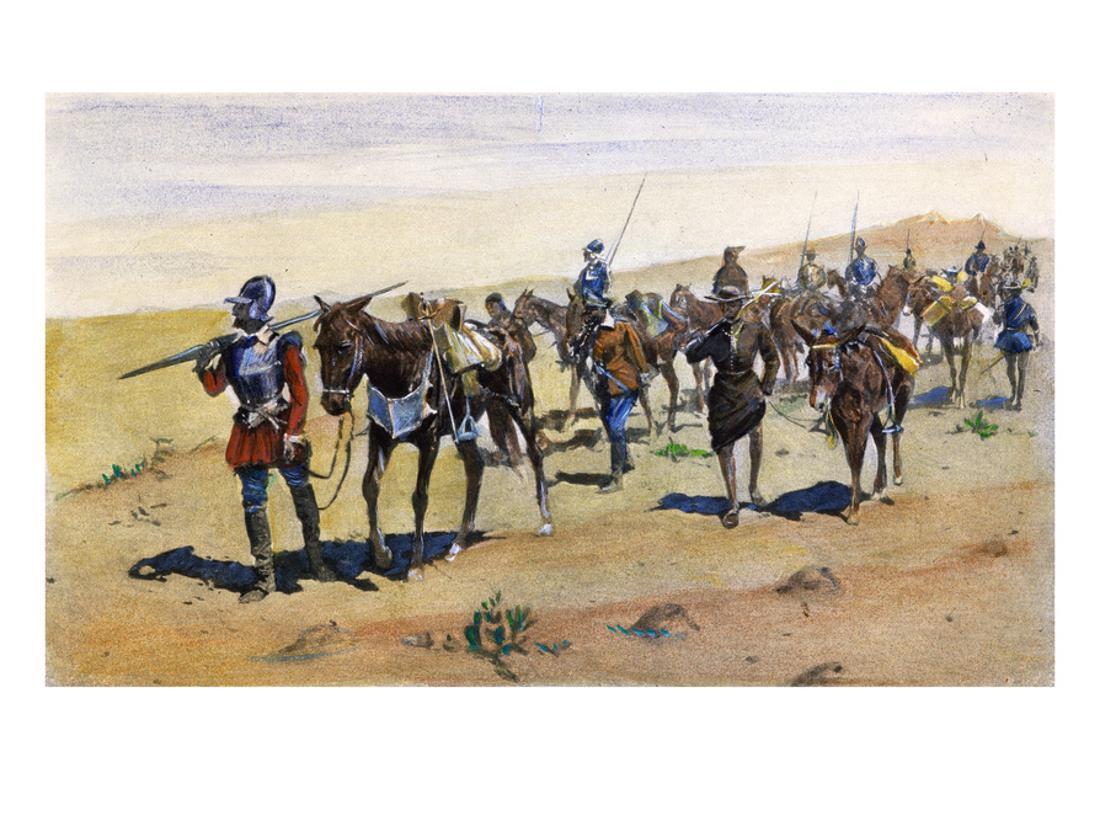

Euro-American interest in exploring Colorado began with the Spanish in the 1540s. Seeking the legendary seven cities of gold, and in efforts to control territory, the Spanish organized many expeditions to explore much of the West, then part of the Spanish Empire. In 1540 famed Spanish explorer Fransico Vasquez de Coronado led an expedition from Mexico that reached the Great Plains but skirted Colorado. However, at least twelve recorded Spanish expeditions explored Colorado between 1593-1780. In 1719, Antonio Valverde y Cosio explored as far as the Platte River and into Nebraska in an attempt to limit French influence on the region. There is no known record of Spanish and the Cache la Poudre River, but it is possible that they traveled in or near the region.

Coronado’s March–Colorado, painting by Frederick Remington, 1898.

American Exploration Begins

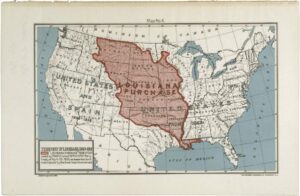

In 1800, the Spanish ceded control of large portions of the West, including what is now northern Colorado, to the French in the Treaty of San Ildefonso. Three years later, in 1803, the French sold nearly the same chunk of land to the new United States in the Louisiana Purchase.

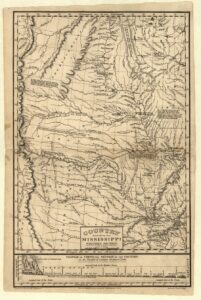

Curious about the new territory, the Americans commissioned several expeditions to explore the area. The first, and most famous, Lewis and Clark Expedition explored north and west along the Missouri River, far to our north through Montana.

The second, and lesser-known, expedition was led by Zebulon Pike (yes, as in Pike of Pike’s Peak) from 1806-1807 and explored south and west. Pike’s expedition was the first American-led exploration of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains of Colorado, but again missed the Cache la Poudre, instead following the Arkansas River through Colorado’s south.

Finally, in 1820, Major Stephen Long (yes, as in Long of Long’s Peak) traveled near enough to give the first recorded reference to the Cache la Poudre River:

”In the course of the day, we passed the mouths of three large creeks, heading in the mountains, and entering the Platte from the northwest. One of these nearly opposite to which we encamped, is Potera’s creek [the Poudre], from a Frenchman of that name, who is said to have been bewildered upon it, wandering about for twenty days, almost without food.

Major Stephen Long

Though the river was known by a different name, Potera’s Creek, it’s been confirmed that Long was talking about the Poudre! Although Long did not follow the Poudre up through what is now the Heritage Area (he was under orders to find the source of the Platte and return along the Arkansas so journeyed south) this is the first record of an organized expedition encountering the Poudre. Edwin James, chronicler for Long’s expedition, also left the first “tourist review” of our region, lumping eastern Colorado in with the future Kansas and Nebraska, which he labeled on the official map as “The Great American Desert,” saying:

”I do not hesitate in giving the opinion, that it is almost wholly unfit for cultivation, and of course, uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture for their subsistence. . . The scarcity of wood, and water, almost uniformly prevalent, will prove an insuperable obstacle in the way of settling the country.

Edwin James

The modern translation: “Farmers steer clear. There is little wood, little water, and little reason to move here.” Ignoring the fact that people had indeed thrived in this region for centuries, this review of the area meant northern Colorado was not high on the list for Euro-American settlers heading out in the first wave of Westward Expansion, or for further organized expedition. Instead, the region was unofficially explored over the next several decades by fur trappers traversing between trading forts.

Watercolor of American Bison by Titan Peale made during Long Expedition of 1820. American Philosophical Society.

Trappers, Traders, and the Naming of a River

Shrouded in legend and a bit of mystery, “mountain men” and fur trappers were real characters in the story of the American West, including through the Cache la Poudre Valley. French and American trappers and traders had been working in and traversing the region since the Louisiana Purchase (and likely earlier) but restrictive Spanish policies kept the fur trade in Colorado sporadic. In 1821 the future of fur trade changed when Mexico gained independence from Spain, ushering in a new era of the fur trade through the Rocky Mountains.

“Wild Mountain Scenery. Making A Cache” by Alfred Jacob Miller, c.1858. The Walters Art Museum

By 1824, renowned trader and founder of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, William Ashley, was holding annual trading rendezvous along the Green River in western Wyoming, drawing traders from places including Colorado’s eastern slopes. Through the 1820s beaver pelts dominated the trade, but by the 1830s the western beaver population had been largely decimated (likely including along the Poudre). This, combined with changing fashion trends in the east, shifted the fur trade to bison robes. As fur trade evolved, a chain of trading forts emerged through the region. In 1833 Bent’s Old Fort was built on the Arkansas River in southern Colorado, followed in 1834 by Fort Laramie in Wyoming, north of present-day Cheyenne (both are now National Historic Sites you can visit). A string of smaller trading forts linked the two, including Fort Vasquez along the South Platte about twenty miles south of present-day Greeley and Fort St. Vrain southeast of Johnstown across the Platte. Because of the Cache la Poudre Valley’s location on the eastern edge of the foothills, south of easy mountain passes, and near several forts and rendezvous points, many trappers used the Poudre canyon, valley, and river as a pathway—as people before them had done for centuries.

While people often think of French “mountain men” or trappers, the fur trade was more diverse—French-Canadians, Native Americans, African Americans, Hispanic, British, Irish, German, Russian, and American trappers worked side by side. Despite the reality of remote and rugged work, the fur trade of the 1820s-1840s was organized with most trappers working in groups and for a trading firm such as Bent or the American Fur Trading Company, and rival firms competing to work with tribes such as the Cheyenne and Arapaho. One such group of trappers gave the Cache la Poudre River its official name …

“Trapping Beaver” by Alfred Jacob Miller, c.1858. The Walters Art Museum

There are several versions of how the Cache la Poudre got its name, and like many stories a dash of legend likely meets fact, but enough evidence suggests the story went something like this: sometime between 1824-1835 a party of trappers traveled along the Poudre River en route to William Ashley’s rendezvous on the Green River. (Some versions say the group was led by Ashley himself). One night they made camp along the river near present-day Bellvue. Waking in the morning they found themselves in deep snow. Forced to lighten their supplies they dug a large pit to cache their supplies and planned to pick them up on their return. According to stories, much of these supplies were gunpowder, and so the river got its name—Cache la Poudre—French for “hide the powder.” By the time the next expedition, led by Captain Henry Dodge, passed in July 1835 the name had stuck. And so, the Cache la Poudre received its final name.

By the 1840s the fur trade was declining, and Fort Vasquez on the Platte was abandoned in 1842. The same year a new group traveled through the region, putting the Cache la Poudre on the map, literally.

Pathfinding—The Fremont Expeditions

John C. Fremont was a military officer and a politician, but perhaps more famously was an experienced American explorer and mapmaker for the U.S. Topographical Engineers. Between 1842-1853 he led five western expeditions, exploring great portions of Colorado, Oregon, California, Nevada, Idaho, and Utah. Accounts of these expeditions, compiled by his wife Jessie, and his precise maps earned him the nickname, “The Pathfinder,” as he found traversable routes over what was considered impassable and unforgiving territory. Fremont crossed the Cache la Poudre far downriver near present-day Windsor during his first expedition in 1842 to map the Oregon Territory, but it was his second visit that put the area on a map.

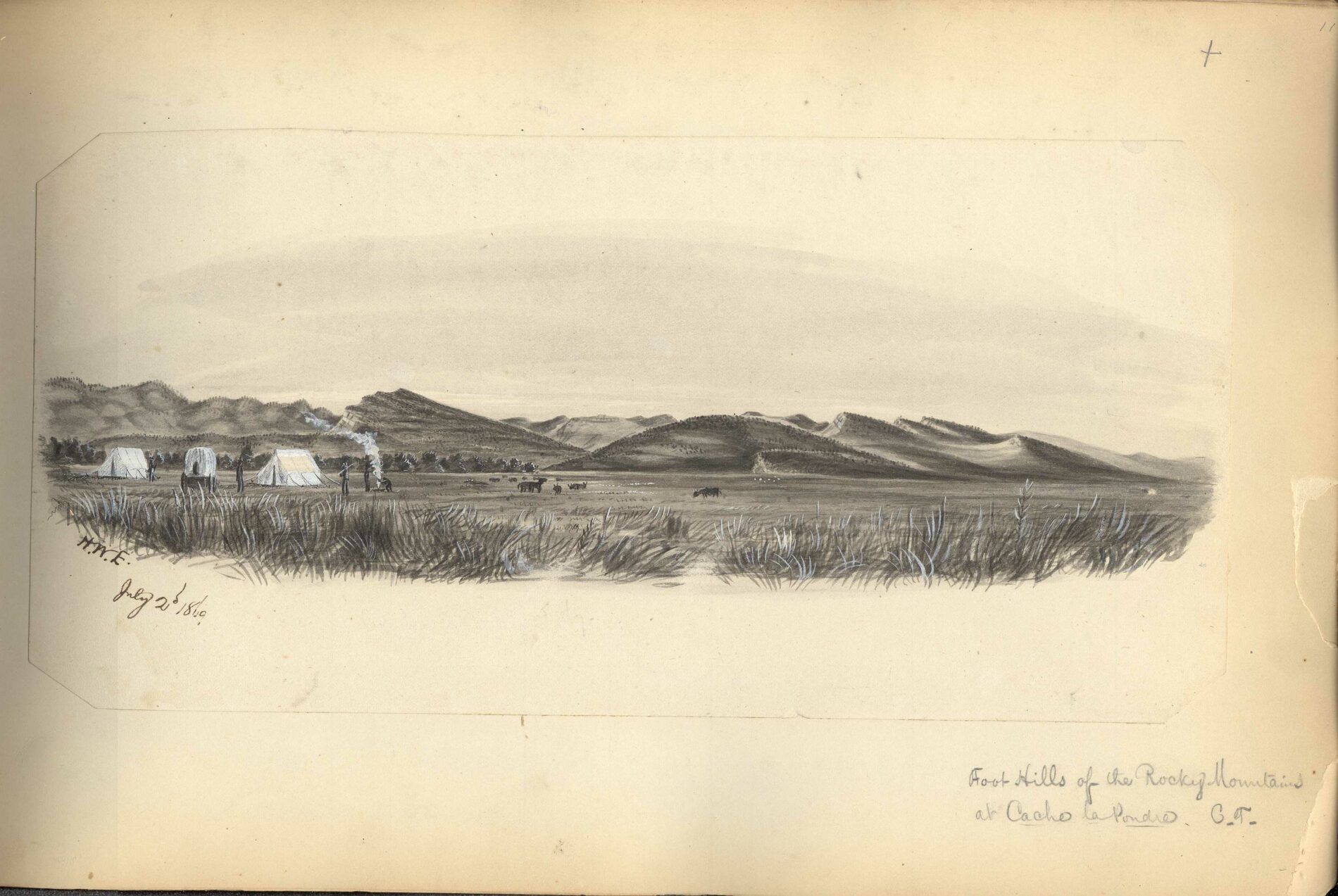

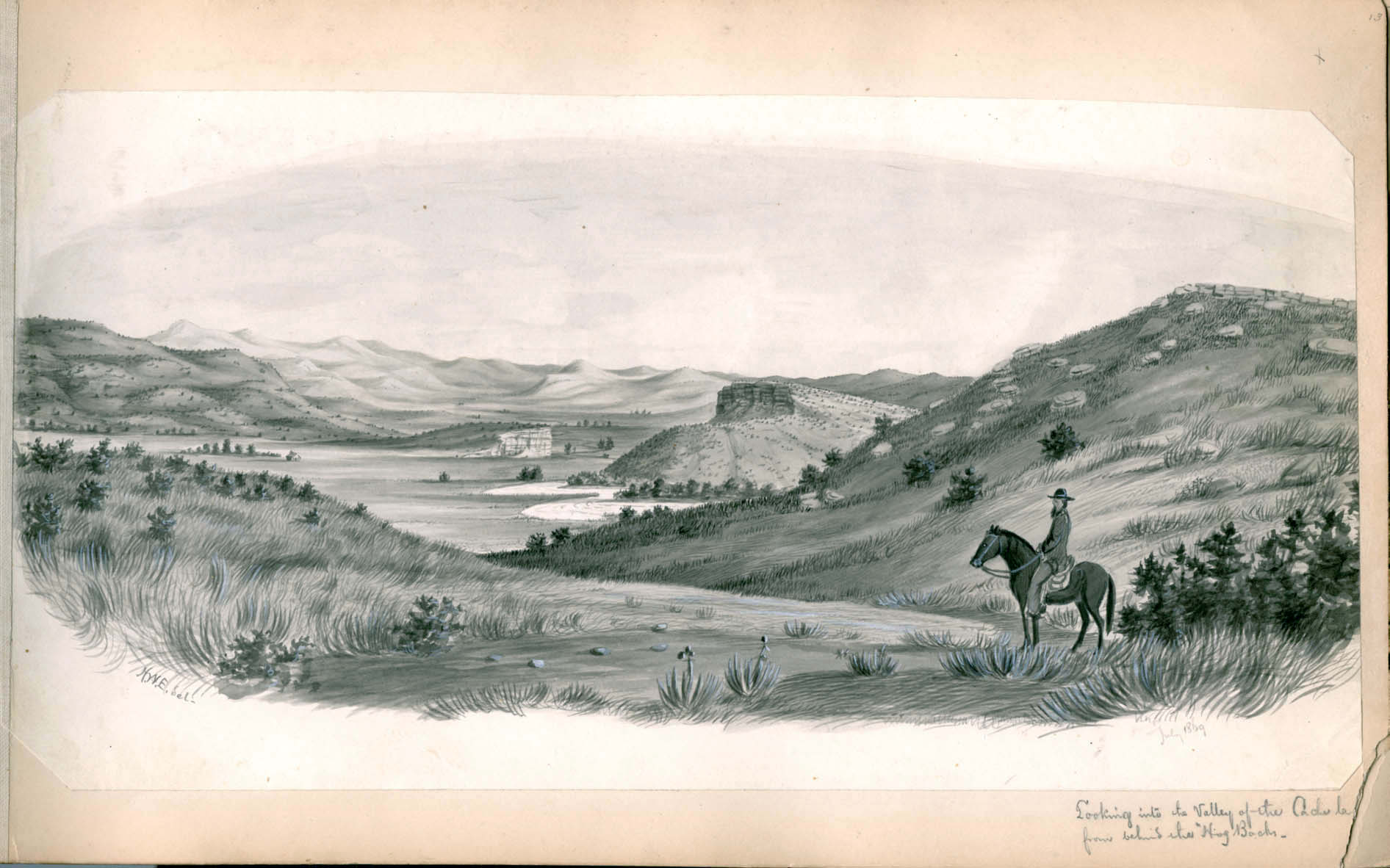

Images of the Cache la Poudre River

While Fremont gifted us with the first written description of the region, there are no known drawings or images of the region until the Hayden Geological Expedition crisscrossed the region in 1869. While Ferdinand V. Hayden made scientific measurements and observations to build a geological understanding and map of Colorado, Henry Wood Elliott, another expedition member and well-known artist and conservationist made sketches. Take a look at Elliott’s drawings of the Cache la Poudre region and ask yourself how the area has changed over the last 150 years or how his images remind you of the area you may have driven, hiked, biked, or lived in.

“Looking towards Cache la Poudre from summit of Stevenson Hill Box Elder Creek, Colorado.” by Henry Wood Elliot, June 1869. USGS

Looking Forward

What we don’t glean from the maps, reports, diaries, and sketches of these early explorers are how the people native to the area felt about these explorers and mapmakers of a land they had already explored. Many of these celebrated explorers in the following decades went on to participate in or initiate massacres of Native Americans or contribute to a narrative that they were savages who did not deserve the land. The descendants of these earliest explorers are still grappling with this reality. For good and ill the stories, map-making, and recording of explorers like Pike, Long, Fremont, Hayden, and unnamed trappers forever changed the future of the river we call the Cache la Poudre River.

Explore!

Plan a Visit to Fort Laramie, Fort Vasquez, or Bent's Old Fort

Although they are all outside the Heritage Area, they are a wonderful addition if you’re planning a trip to the region or, if you live here, a great trip outside the Heritage Area to explore more of our history.

Follow Fremont's Path

Spend a day driving and walking Fremont’s expedition through the area from the Fort St. Vrain marker to Gateway Natural Area. Although there are no markers to guide your journey, you can embrace the unmarked path that Fremont would have experienced and follow the route as outlined in the history above!

Spend Time at Gateway Natural Area

At Gateway Natural Area the North Fork of the Poudre meets the main river. From this spot in the Poudre Canyon Fremont’s expedition veered north. It’s a wonderful way to experience a bit of the Cache la Poudre River and get a taste of the canyon. We love the walking and hiking trails that link to this Natural Area, the nature playground, easy access to splash or fish in the Poudre (including a designated kayak launch), and the picnic area and grassy spaces to enjoy!

Gateway Natural Area is open daily, dawn to dusk.

Daily passes at Gateway cost $8/vehicle and can only be purchased at Gateway (card only). (Poudre River Library District and Wellington Library District cardholders can check out passes from their library).

Find Space for Art

Do you have a favorite spot in the Heritage Area? It could be along the Poudre Trail, next to a reservoir or pond, in the foothills, or even just a spot special to you. Spend some time in that special spot, take a look around, and, in honor of the Hayden Expedition, create some art from what you see. It could be a sketch or painting or maybe a photograph, poem, story, song, or memory.

Need some ideas of where to go? Check out the explore page!

References

“A Brief History of the Fur Trade.” From History Colorado.

“The Fur Trade in Colorado.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

Jackson, Donald and Mary Lee Spence (ed.) “The Expeditions of John Charles Fremont.”

“John C. Fremont.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

McKinney, Kevin C, editor. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Digital Archive: Previously Unpublished Sketches by Henry W. Elliott United with the Preliminary Field Report of The United States Geological Survey of Colorado and New Mexico, 1869, by F. V. Hayden.

“Spanish Exploration in Southeastern Colorado, 1590-1790.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

Spence, Mary Lee, and Donald Jackson, editors. Expeditions of John Charles Fremont: Volume 1 Travels from 1838 to 1844. University of Illinois Press, 1970.

“Stephen H. Long.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.

“Stephen H. Long.” Nebraska Studies from Nebraska Public Media.

“Zebulon Montgomery Pike.” Colorado Encyclopedia from History Colorado.