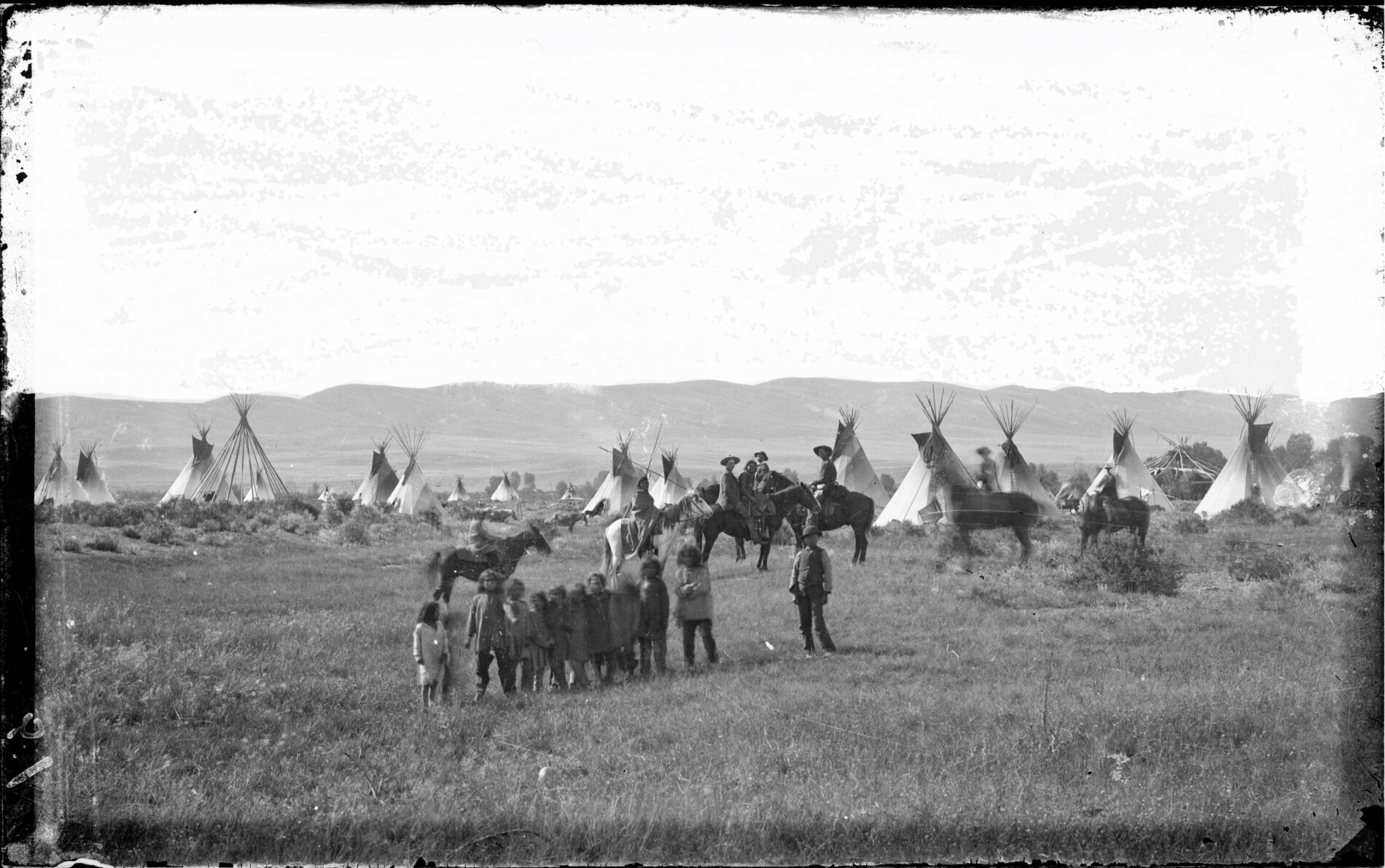

Long ago, in this place, water flowed down from the snowcapped Rockies, tumbling through a canyon before emptying out on vast plains. A river, one of many, sustained life. Cottonwoods grew along its banks and chokecherry bushes blossomed, producing ripe purple berries later in the summer. Birds flocked and fish jumped. Muskrat, beaver, foxes, coyotes, rabbits, and squirrels scurried along the river’s banks for a drink. Deer and elk watched from the bends. Bison, even, roamed beside it as it flowed through prairie grasses, meandering toward a greater river. And people splashed, laughing as they crossed the river, gathering its water in skins or sealed baskets.

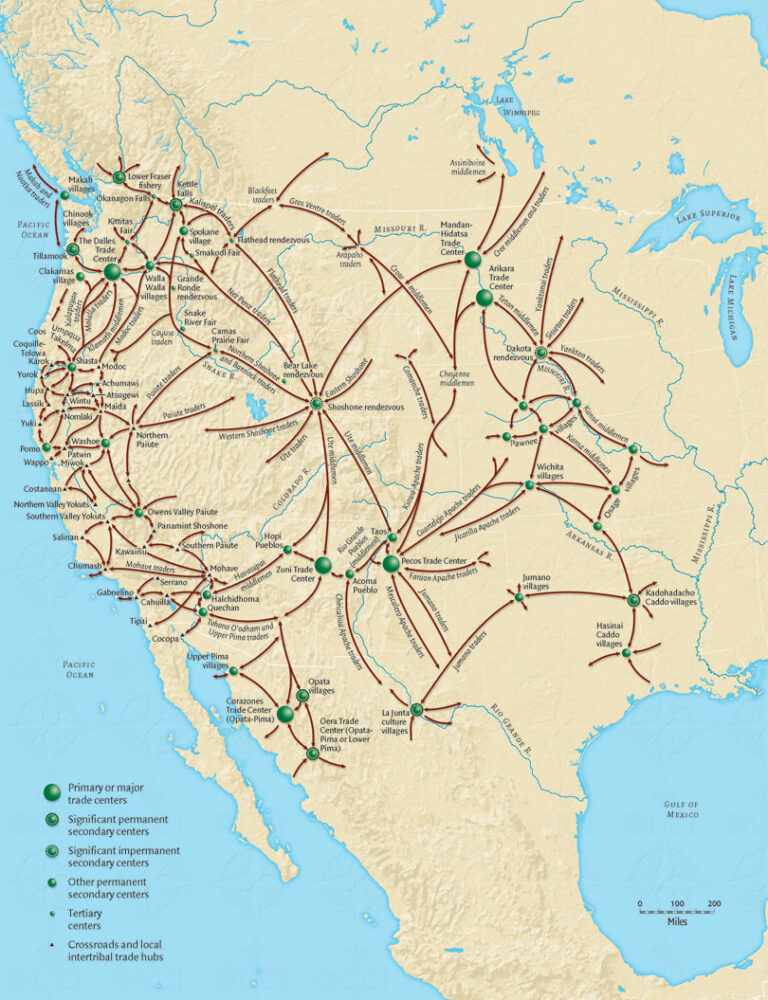

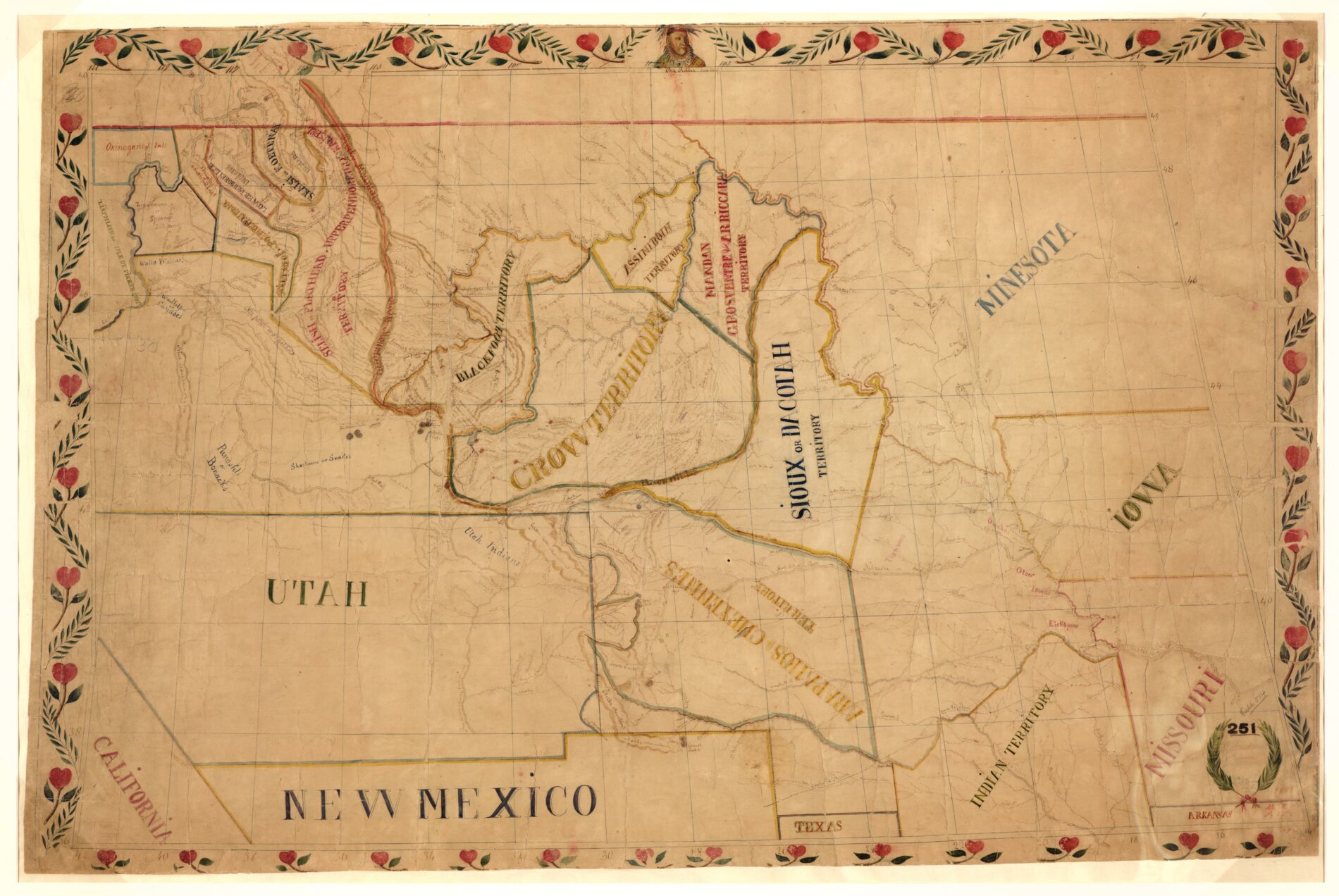

The land we now call the Cache la Poudre River watershed has long been the Homeland of many diverse groups of people. But long before the river was called by that name it had others, in many languages, as it guided and sustained many tribes and nations. People have been drawn to the Poudre River for over 12,000 years, Ancient People—the Ancestors or Ancient ones—lived and traveled here (you can read more here). Their diverse descendants also made their homelands across large amounts of the foothills, mountains, and plains of this region including the Hinono’eiteen (Arapaho), Tsis tsis’tas (Cheyenne), Nʉmʉnʉʉ (Comanche), Caiugu (Kiowa), Čariks i Čariks (Pawnee), Sosonih (Shoshone), Oc’eti S’akowin (Lakota) and Núuchiu (Ute) Peoples.

Do you know who occupied this land before you? Who lived, worked, died, and thrived along the rivers, mountains, and plains before this land was colonized, and who are still here despite all odds?