The founding of Union Colony in 1870 marked a turning point in the Cache la Poudre River Valley. For centuries, these plains had been home to Native peoples and their ancestors, and more recently a crossroads for explorers and traders. When settlers from the eastern United States arrived, they brought with them ambitious visions of community and cultivation, but they soon discovered that life on Colorado’s arid frontier demanded new solutions. Above all, Irrigation would determine whether the colony could survive. This story of water, land, and people remains at the heart of the Cache la Poudre National Heritage Area today.

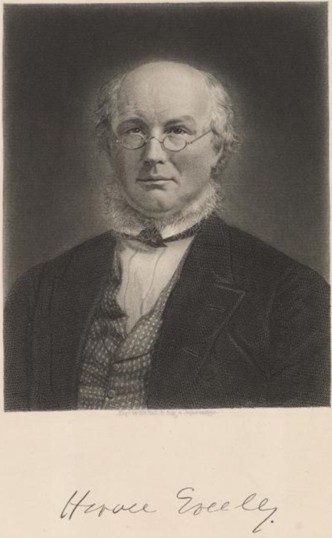

After the Civil War (1861-1865), the New York Tribune became one of the loudest voices urging Americans to look westward. Its publisher, Horace Greeley (1811-1872), believed the Rocky Mountain West promised health, opportunity, and fertile land for those willing to work it. Through fiery editorials, he painted the West as a place where families could leave behind crowded cities and build new, self-reliant communities. His words struck a chord with war veterans, working-class readers, and would-be homesteaders searching for fresh starts.

”Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.

Horace Greeley, New York TribuneJuly 13, 1865

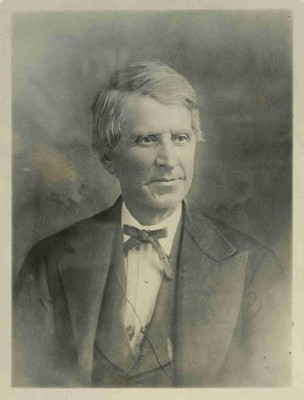

Greeley’s call to “Go West” was not just the rhetoric of a removed dreamer. In 1859, during the height of the Colorado Gold Rush, he traveled through the Rockies and along the Front Range, later publishing his experiences in An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859. His vivid accounts of the Cache la Poudre Valley caught the attention of Nathan Meeker (1817-1879), a New York Tribune correspondent that Greeley had once hired to report on the Civil War. Meeker, already fascinated by the social theories of French thinker Charles Fourier, began to imagine a farming colon on the plains where cooperation, temperance, and hard work could shape an ideal community.

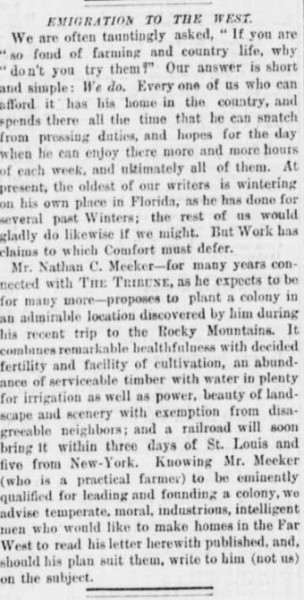

A decade later, Nathan Meeker returned to Colorado as the New York Tribune’s agricultural editor. By 1869 he had developed a detailed plan for a western farming colony and secured Greeley’s support. That December, he published a call in the New York Tribune inviting settlers who shared his ideals of temperance, religious faith, cooperative agriculture, and community spirit. Within months, his bold proposal had set in motion the founding of Union Colony the following spring.

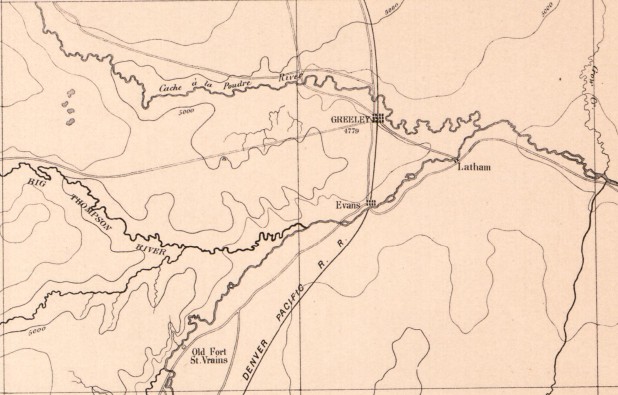

Meeker’s announcement in the New York Tribune sparked immediate interest. Within weeks, about sixty readers gathered with him in New York to discuss the plan. Out of this meeting came the Union Colony Corporation, which began raising money through initiation fees and donations for a land purchase. In February 1870, Meeker and a small group of associates traveled to Colorado Territory to choose a site. After surveying several locations, they selected land along the Cache la Poudre River, about four miles upstream from its meeting with the South Platte.

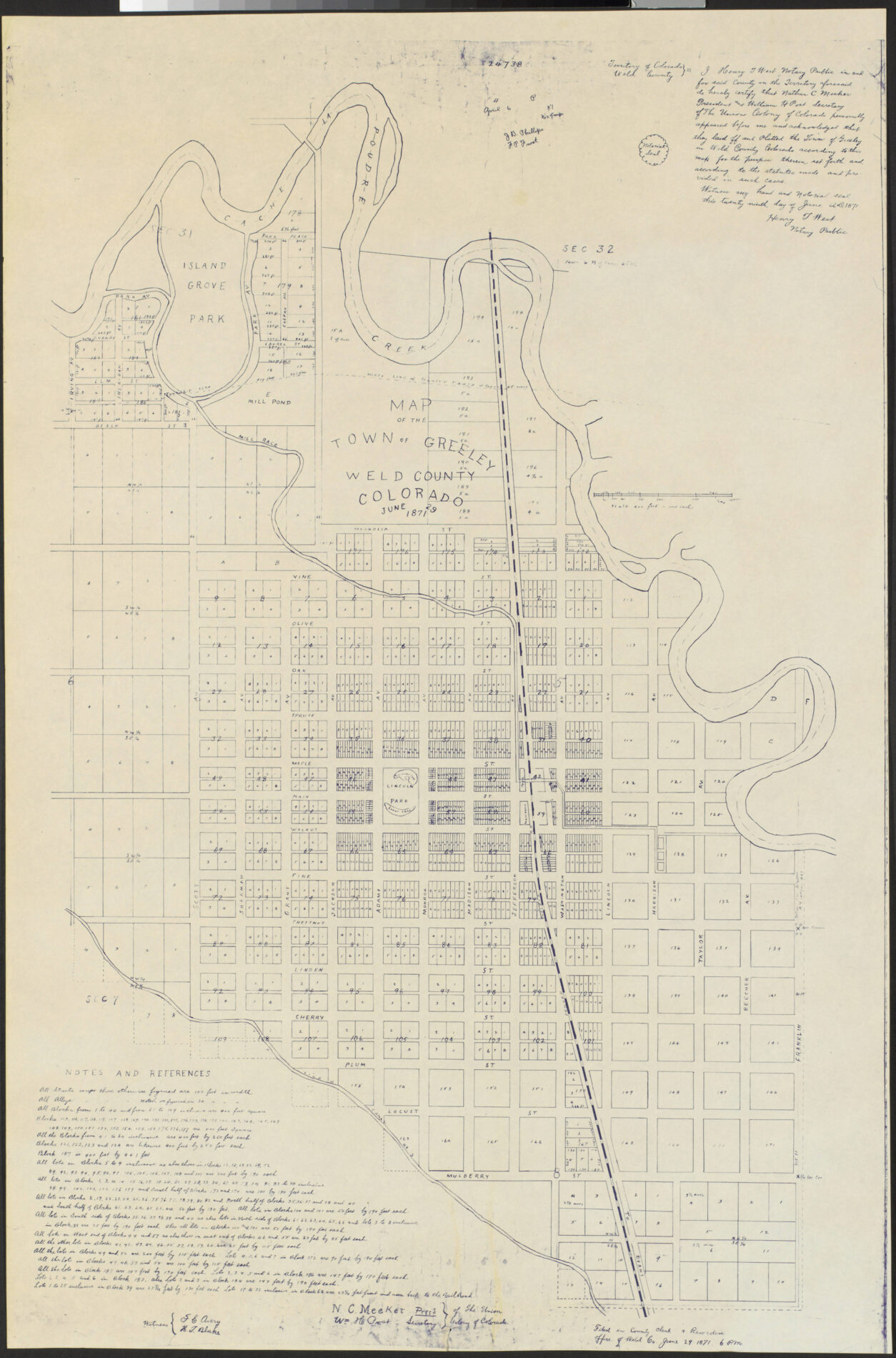

Clipped map of northern central Colorado from the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division (1877)

Meeker and his associates secured more than 9,000 acres from the Denver Pacific Railway and negotiated rights to an additional 60,000 acres of public domain through the U.S. General Land Office. By April 1870, the first settlers began to arrive. The reality of the dry plains, however, proved harsher than the idealized vision many had read in the New York Tribune. Some colonists left almost immediately, forfeiting their investments, and about ten percent asked for refunds. Yet by autumn the colony still counted around 500 residents, enough to give Meeker’s cooperative experiment a foothold along the Poudre.

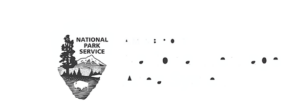

Map of the Town of Greeley from Colorado State University Libraries’ Carpenter (Delph E. and Family) Papers (1871)

From the very beginning, Union Colony’s survival depended on irrigation. Meeker and the other leaders envisioned four major ditches, but limited funds forced them to scale back to two. The first, the ten-mile-long Greeley Number 3 called the “town ditch” was completed by June 10, 1870, though it soon needed enlargement to meet demand.

The second project, the Greeley Number 2 or “farmer’s ditch,” was far more ambitious. It aimed to bring water to higher bench lands beyond the river bottoms. Union Colony began construction of the ditch in the fall of 1870. Lacking experience with such large-scale engineering, however, the colonists turned the work over to the newly formed Cache la Poudre Irrigation Company, whose expertise ensured the ditch’s completion.

Canal Number 2 in Weld County, Colorado from the City of Greeley’s Permanent

Union Colony lacked the resources to build two of its planned projects. Greeley Number 1 would have diverted water upstream of the farmer’s ditch, and Greeley Number 4 would have drawn from the Big Thompson River. Instead, both were taken up by the Colorado Mortgage and Investment Company of London. The proposed Number 1 became the Larimer and Weld Canal in 1879, later organized as a mutual ditch company. The Number 4 plan was realized two years later as the Greeley and Loveland Canal, owned by the Greeley and Loveland Irrigation Company.

Even with its scaled-back ditch system, Union Colony managed its first harvest in 1870, establishing irrigation as the heart of its identity. That fall, Horace Greeley himself visited the fledgling settlement. On October 12 he was welcomed with a community celebration, complete with a platform and benches built outside the new Greeley Tribune office. From there, he praised the colonists for choosing farm life over city life, repeating one of his familiar themes:

”Our people were habitually gregarious and too fond of flocking to our cities and villages, where they help to swell the ranks of squalid misery and every manner of crime, and pestilence, and want, and all the evils that infest our densely populated places everywhere.

Horace GreeleyDenver Daily Colorado Tribune, October 15, 1870

During his visit, Greeley was also taken to the head of the Number 3 ditch, the lifeline of the community, to see water flowing across the dry plains. By then, Meeker’s colony had begun to shape the region’s agricultural economy. Yet the challenges of living on the Poudre were far from over. What began as a struggle against nature soon shifted into struggles between neighbors.

Less than two years later, Union Colony faced fierce competition from its new neighbors of Agricultural Colony. Their disputes over irrigation water erupted into the 1874 Water Wars, marking the next stage in the valley’s history. These conflicts underscored a truth still visible in our National Heritage Area today; the fate of communities here has always been bound to the shared waters of the Cache la Poudre River.

Explore More!

Consider visiting sites in our heritage area like Centennial Village Museum, the Greeley History Museum, and the Meeker Home Museum!

References

Leonard Spinrad and Thelma Spinrad. Speaker’s Lifetime Library. West Nyack, NY: Parker Publishing Company, 1979, 155.

Hobbs, Gregory J., Jr., and Michael Welsh. Confluence: The Story of Greeley Water. Greeley, CO: City of Greeley, 2020.

“From Our Travelling Correspondent,” Denver Daily Colorado Tribune, October 15, 1870. Quoted in Gregory J. Hobbs Jr. and Michael Welsh, Confluence: The Story of Greeley Water. Greeley, CO: City of Greeley, 2020.

“Emigration to the West.” New York Tribune, December 4, 1869. Accessed via Colorado Virtual Library. https://www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org/resource-sharing/state-pubs-blog/time-machine-tuesday-the-union-colony-at-greeley/

Greeley, Horace. Horace Greeley Papers: Correspondence; Bound, 1838-1852, 1894. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss23937002/.

City of Greeley Museums, Permanent Collection, AI-3146. “Nathan Meeker, 1870.” Accessed via Colorado Encyclopedia: https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/image/nathan-c-meeker

Geological And Geographical Survey Of The Territories, U.S, and F. V Hayden. Geological and geographical atlas of Colorado and portions of adjacent territory. New York: J. Bien, lith, 1877. Map. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/gs08000146/.

Meeker, Nathan Cook and William H. Post. “Map of the town of Greeley.” 1871. In Carpented (Delph E. and Family) Papers. Colorado State University Libraries. https://archives.mountainscholar.org/digital/collection/p17393coll150/id/1202