As the Colorado snowpack starts to melt and rivers and streams across the state begin to rise, its important to remember to Play It Safe on the Poudre!

The Cache la Poudre River offers many miles of incredible recreational opportunities – the scenic river runs from mild (class I-II) to wild (class V), attracting people from around the country to its beautiful waters. However, most people do not understand the dangers that exist while recreating on the river.

The Poudre River presents numerous hazards. Broken or low-hanging tree branches, hidden beneath the water, can snag a person out for a lazy afternoon tubing trip. Freezing waters made cold by spring runoff can cause a person to react slowly, when quicker action is needed, or possibly suffer hypothermia. And deceptively fast-moving waters pose a drowning risk to even the most experienced swimmers.

“The Poudre River is a source of local pride that draws thousands to its waters each year. We wouldn’t dissuade peoples’ love for it and what it represents. But the river is equal parts beautiful and destructive. Its power is easy to underestimate, and river-related tragedy can befall anyone at any time,” said former Poudre Fire Authority spokeswoman Madeline Noblett.

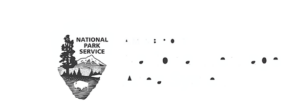

The Play It Safe on the Poudre program raises awareness about approaches to recreating on the river in safe and sustainable ways, and helps to build the capacity of the Poudre Fire Authority and Larimer County rescue teams. The program also calls attention to the history of in-river structures that represent hazards to recreation.

Play It Safe on the Poudre principles:

- Wear a life vest

- Use proper floatation devices

- Wear shoes

- Wear a helmet

- Don’t tie anything to yourself or your tubes

- Safe to go?

- Know the weather and water conditions

- The water is melted snow – it’s always cold!

- Avoid rocks, branches, logs and debris in the river

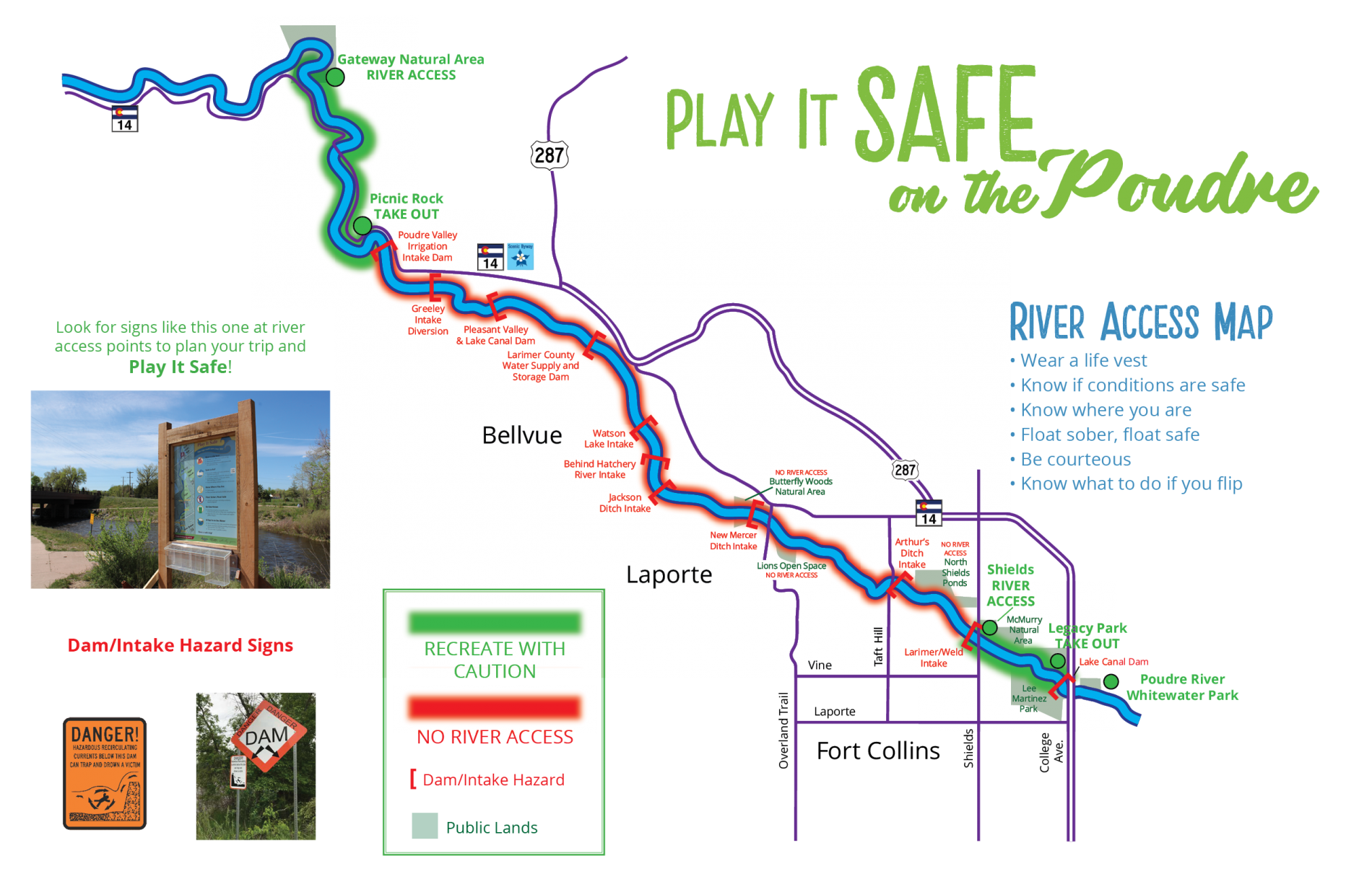

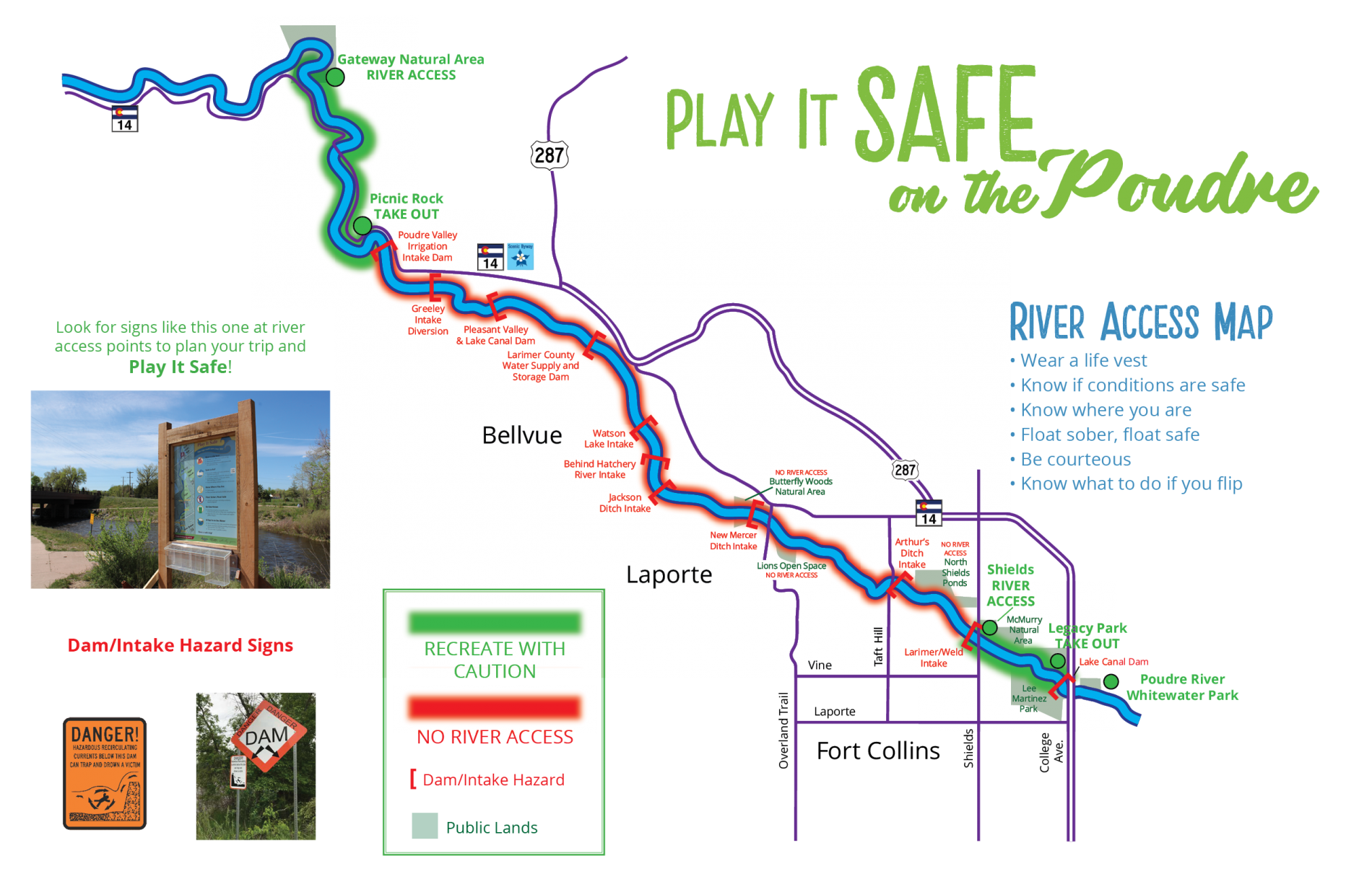

- Know where you are

- Take a map

- Plan your take-out location before you get in the river

- Float sober, float safe

- Alcohol and drugs impair judgement

- Be Courteous

- Pack it in; Pack it out

- Share the river

- What if you flip?

- Don’t stand up in the river; avoid foot entrapment

- Float on your back with feet pointing downstream and toes out of the water

- Use your arms to paddle to shore

Download a River Access and Safety Map

Other representatives who have taken part in the group’s efforts represent: Poudre Fire Authority; multiple departments within the City of Fort Collins, including the city’s Natural Areas Department; Larimer County; the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office and Larimer County Emergency Services; Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and more.

For more info please visit www.poudreheritage.org/playitsafe