By Chloe Lewis, SWCA Environmental Consultants

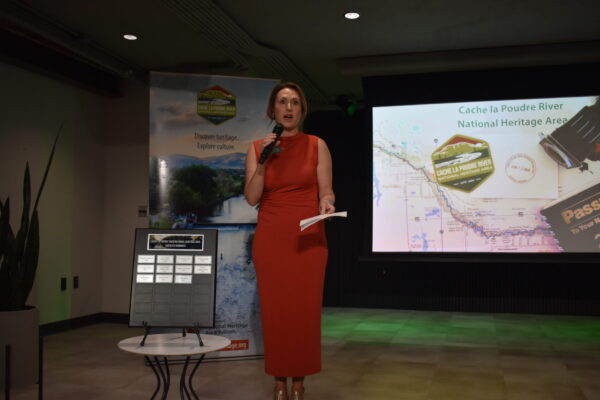

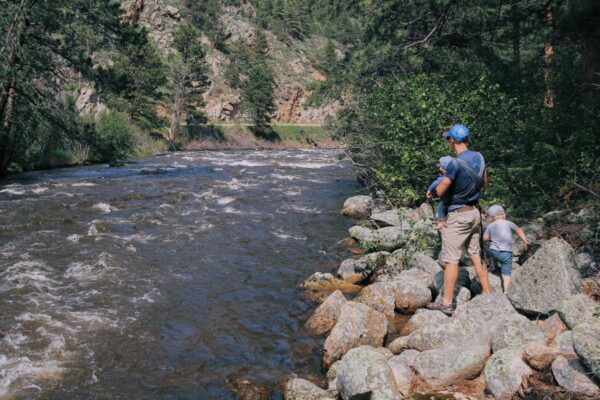

Across the West, communities are facing intensifying water challenges driven by growth, drought, wildfire, and high-water events. Addressing these pressures requires more than strong technical analysis—it requires shared learning, the development of long-term goals, and sustained collaboration. Community events, such as the Poudre River Forum, are essential to balancing ecological health, water use, heritage values, and community needs.

For watershed restoration projects, effective community engagement brings together agencies, water managers, residents, nonprofits, agricultural producers, and municipalities to shape a unified path forward for watershed health. When diverse voices come together, the process becomes more than planning—it becomes an opportunity for communities to deepen their understanding of their watershed systems, the stressors affecting them, and the actions needed to preserve them for future generations.

The lesson for watershed and environmental restoration efforts everywhere is clear: meaningful community engagement is not supplemental to the work—in many cases it is the work.

For example, the recent River Health Assessments along the Poudre River can serve as a unifying foundation for collaboration by providing a shared, science-based understanding of current conditions, stressors, and opportunities for improvement. Future conversations can be grounded in this shared, science-based understanding while also incorporating community values. The assessment helps partners align around a common vision for river health and prioritize coordinated, achievable restoration actions.

Engaging a consulting team, such as SWCA Environmental Consultants (SWCA), can help prioritize and facilitate broad public participation from the project outset. Early engagement creates space for stakeholders to define shared values, identify watershed restoration priorities, and contribute local knowledge that strengthens technical analysis.

”If people don’t see their voice reflected in the outcomes, the plan won’t live beyond its adoption. Engagement is what ensures a plan can continue to guide action.”

SWCA Environmental Consultants

This approach builds ownership—not just awareness. It fosters collective learning and positions community members as active stewards of their watershed rather than passive recipients of a plan.

Collaboration Drives Lasting Outcomes

Watersheds do not follow jurisdictional boundaries, and no single entity controls all factors that influence water quality, habitat health, and resilience. Counties, municipalities, utilities, landowners, and nonprofits must work together to protect and restore shared resources.

The Larimer County Water Plan, led by the County and supported by SWCA’s water resource and community engagement specialists, provides a recent example of successful and effective collaboration around water resource planning. Through facilitated dialogue, participants identified priorities that extend beyond infrastructure to include water literacy, habitat preservation, watershed stewardship, risk management, and alignment between land use and water planning. These shared commitments strengthen trust across sectors and create a durable foundation for restoration projects, funding partnerships, and adaptive management over time. The final plan is available on Larimer County’s website.

Ultimately, restoration in the Poudre River watershed will be most successful when it is grounded in science, informed by community learning, committed to sustainability, and carried forward by a culture of stewardship.

SWCA is grateful to participate in the 2026 Poudre River Forum and connect with community members in person. Learn more about how SWCA can bring their technical expertise and professional community engagement expertise to your next project: SWCA Environmental Consultants

The Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area is grateful for SWCA Environmental Consultants’ support of the Poudre River Forum. Learn more about how to get involved here.

dangerous mushrooms?

dangerous mushrooms?