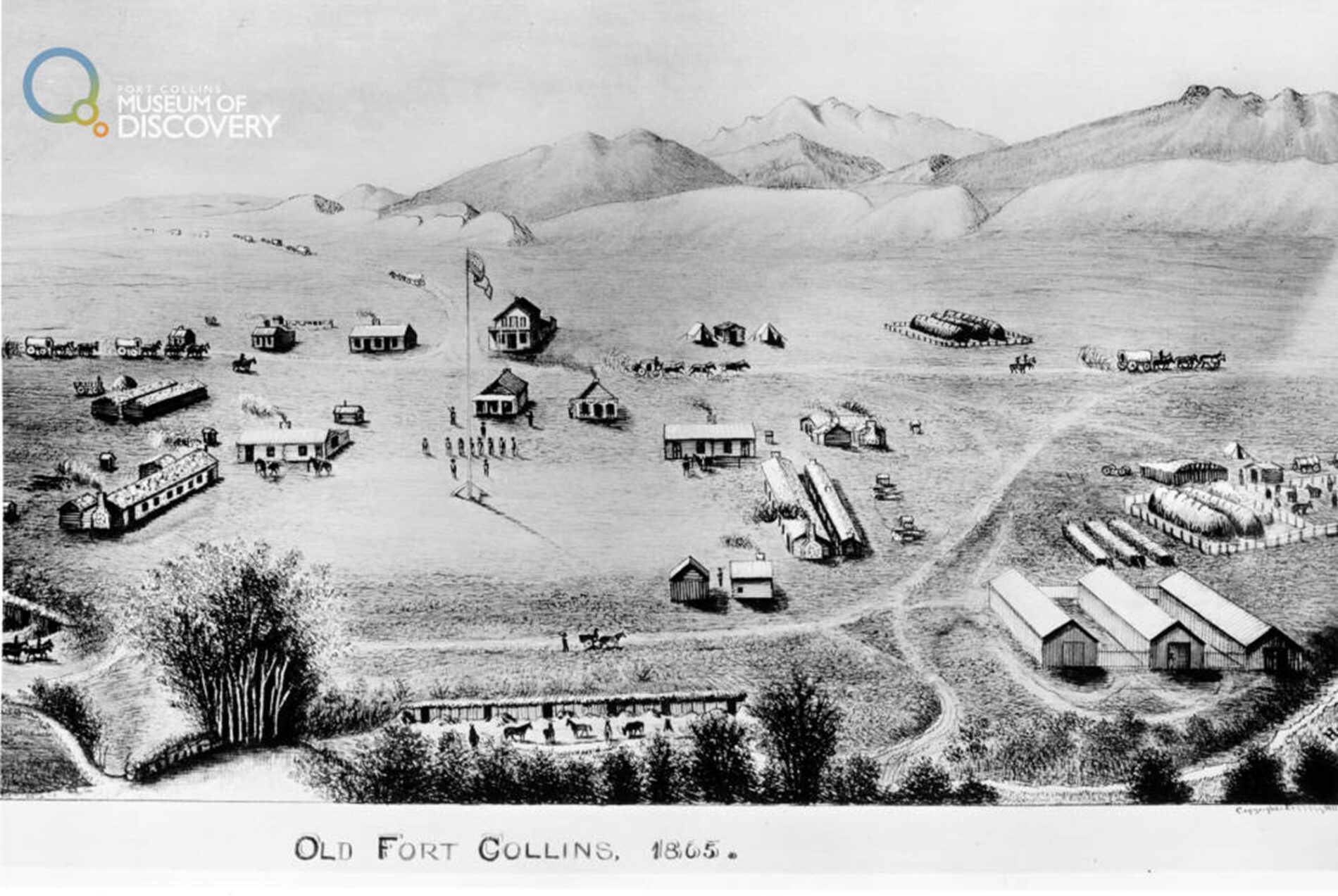

The story of Fort Collins Agricultural Colony begins with earlier chapters of life along the Cache la Poudre River. For generations, Native peoples and their ancestors made their homes here. Later, explorers and traders followed the river’s course, mapping its corridor into national awareness. By the mid-1800s, the U. S. Army established Camp Collins on the Poudre, around which a small supply town took shape.

When the fort closed in 1867, some residents stayed and were joined by homesteaders, Civil War veterans, and ranchers who began craven out modest farms along the river. They dug *crude ditches, relied on each other for survival, and created the outlines of a farming community in an arid valley. Yet these scattered efforts soon gave way to something more ambitious. The 1870s bought a wave of planned projects including colonies, a college, and canals that transformed Fort Collins from a frontier outpost into a deliberately designed agricultural town. These changes linked people, place, and water in ways that still defines the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area and greater region of Northern Colorado.

The first organized attempt to build a colony on the Cache la Poudre River came in 1869, three years before the Agricultural Colony. A group of settlers from Mercer County, Pennsylvania, led by Reverand W.T. McAdam, journeyed west with Civil War veterans and families in tow. Among them was Alfred A. Edwards, who later recalled their journey:

”Reverand McAdam purchased fourteen thoroughbred mares, together with four mules and a covered wagon to convey our outfit.

Alfred A. EdwardsFort Collins Express, 1935

Encouraged by letters from Captain James W. Hanna, a former officer stationed at Camp Collins who praised the valley’s potential, the Mercer group settled near what is now Grandview Cemetery in City Park. They formed the Mercer Pole and Ditch Company to build an irrigation system that could turn the dry prairie into farmland. But ditch digging was slow, costly, and exhausting. Within months the colony ran out of funds and began to unravel. The planned irrigation feature would not be completed until it was recharted in 1872, well after the dissolution of Mercer Colony.

Although short-lived, the Mercer Colony was a turning point. It demonstrated both the optimism of settlers who believed irrigation could unlock the land’s promise, and the sobering reality of the challenges ahead. While Mercer failed, its efforts foreshadowed the more sustainable projects that would soon follow and gave Fort Collins its first taste of colonization by design.

New Mercer ditch and Larimer County Number 2 ditch, 1966 from the Coloradoan Collection, archive at the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery.

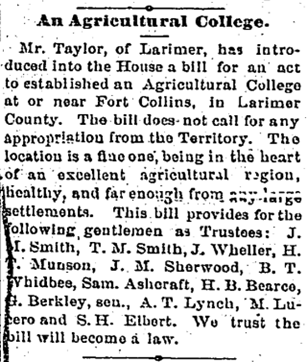

While Mercer Colony faltered, another experiment in building community took root: Colorado Agricultural College, known today as Colorado State University. The idea began even before statehood, as farmers and merchants around Camp Collins pushed to secure a land-grant college for their town. In 1867, Representative Harris Stratton introduced a bill to create the school, though his effort failed due to confusion over federal regulations. Just three years later, Representative Mathew S. Taylor succeeded. On February 11, 1870, Territorial Governor Edward McCook signed the act establishing the college.

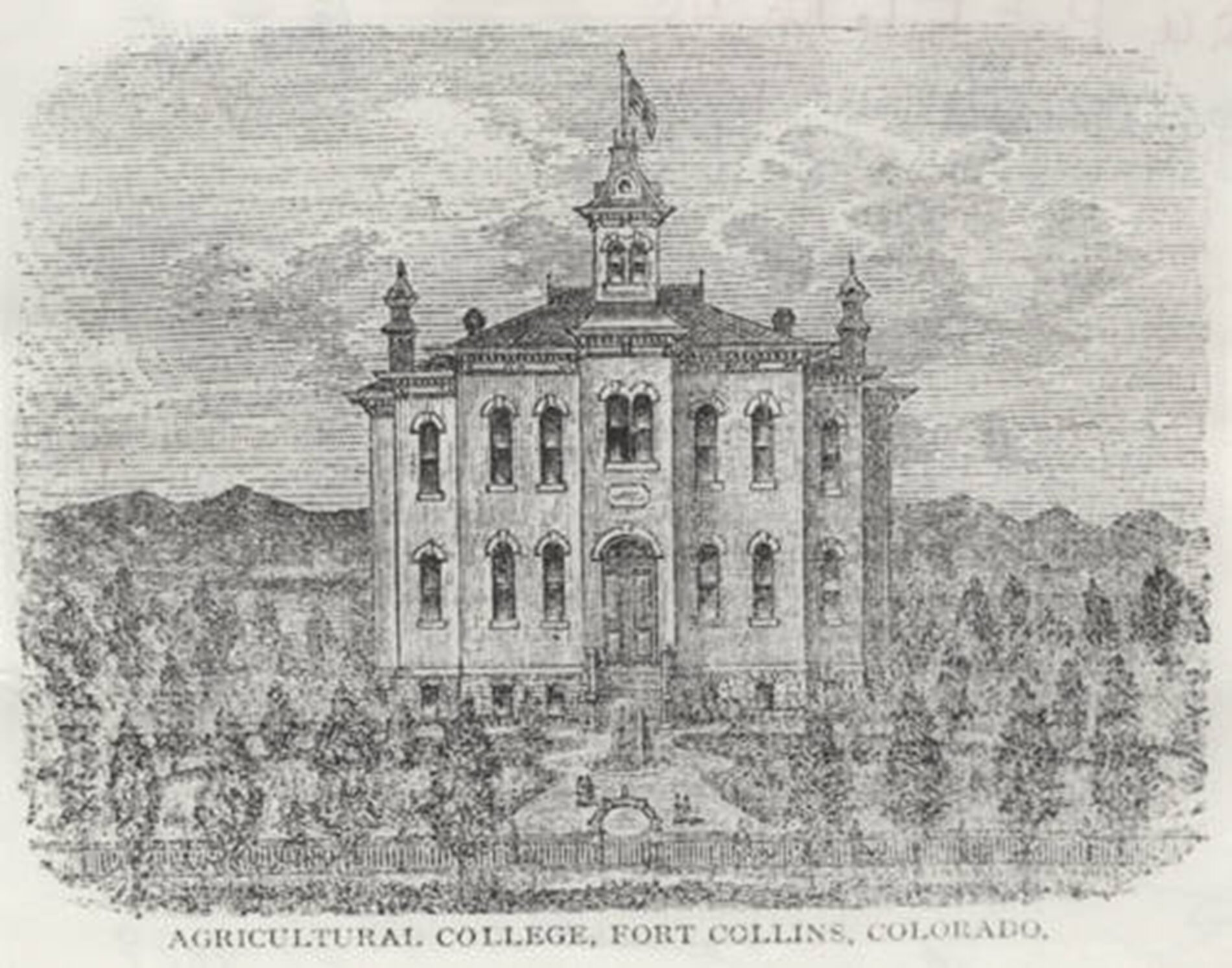

At first the college only existed on paper. Colorado was still a territory, and federal support through the Morrill Act could not be tapped until after statehood in 1876. Still, local leaders pressed forward. A State Board of Agriculture was appointed, land donations were gathered, and by 1878 the cornerstone of the Main Building was laid. The first dormitory followed in 1881, a chemical laboratory in 1882 and other facilities soon after.

Old Main, Colorado State University, 1879 from the Historical Collection at the archive at Fort Collins Museum of Discovery.

Classes began in 1879 under the college’s first president, Elijah Evan Edwards, a Methodist minister. Students studied reading and arithmetic alongside hours of daily labor, reflecting the practical mission of a frontier farming school. Over time, the curriculum expanded to include agricultural chemistry, engineering, and household economy. Edwards and the following president Charles L. Ingersoll advocated for broader liberal education, including subjected such as languages and psychology, though they often clashed with a Board still dominated by farmers.

The college’s survival was never certain. In 1877, one legislator dismissed the entire enterprise declaring:

”I feel as if it was throwing the money away, for you never can make Colorado an agricultural state. It is only fit for a cow pasture and mining.

Representative Jim CarlisleLegislative Session, 1877

Yet with federal lifelines like the Hatch Act of 1887, which funded agricultural experiment stations, and the second Morrill Act of 1890 providing cash support the college endured. By the end of the century, Colorado Agricultural College had become more than an institution of learning. It anchored Fort Collins as a center of agricultural science and research, linking local farming to broader national education.

However, the turning point in Fort Collins’ growth that would allow the college to thrive came in 1872 with the founding of the Agricultural Colony. Inspired by Union Colony‘s established settlement downstream in Greeley, but largely shaped by local boosters, the project was led by General Robert A. Cameron along with community leaders like Joseph Mason, Benjamin Eaton, and Franklin Avery. Unlike Greeley’s Utopian religious experiment, Agricultural Colony was more pragmatic. Its purpose was to attract settlers, establish businesses, and secure a lasting community based in agriculture.

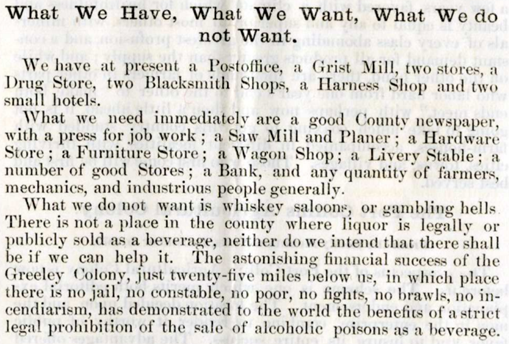

That year, Congress opened former military reservation land around the area for homesteading and *preemption claims. The Larimer County Land Improvement Company, known simply as Agricultural Colony, moved quickly to organize. Membership certificates sold for $50 to $250, granting holders lots in the new town, water rights, and in some cases both businesses and residential property. Promotional flyers promised opportunity for “industrious people” while vowing to keep out saloons and gambling halls.

In December 1872, the first drawing of lots distributed a fifth of the available parcels. By February 1873, Fort Collins was officially incorporated. Businesses sprang up and a post office was established. By April 1873, the Larimer County Express became the community’s first newspaper. The colony also attracted prominent settlers like Avery himself, who would go on to found First National Bank of Fort Collins, and Jacob Welch, an early merchant.

Life in the Agricultural Colony was not without hardship. In 1873 an English Traveler, Isabella Bird, dismissed the town as too “utilitarian” and complained of swarms of locusts that would devastate crops for years. Attempts to ban liquor also faltered, as saloons and pool halls opened despite the trustees’ original vision. These struggles reflected the realities of life on the frontier. Ultimately, Agricultural Colony succeeded where earlier efforts had failed by providing a grid, civic institutions, and a stable population base that would carry the town into the future.

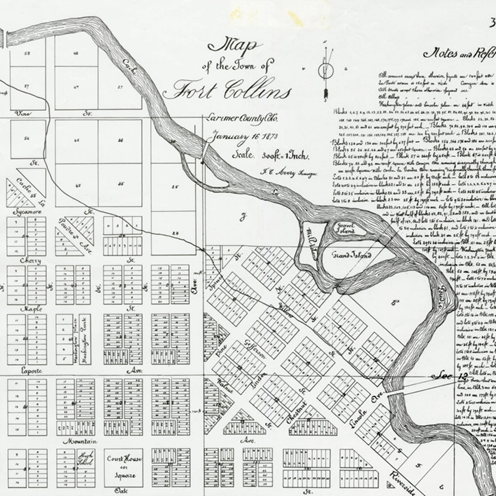

Franklin Avery, a skilled young surveyor who helped start Union Colony, was hired to design Agricultural Colony. His plan divided the settlement into two parts: Old Town aligned with the river and state road while New Town was laid out square with the compass. He named street after colony founders and eastern trees, patterns that strive in today’s cityscape. Wide streets, like College Avenue and Mountain Avenue, gave the town a distinctive character.

Agricultural Colony’s thriving still depended on reliable water. The Mercer Ditch had shown both the possibilities and limitations of irrigation. To make Fort Collins truly sustainable, more and larger canals were needed to move water farther across the plains. Acting on this knowledge, colony leaders awarded three contracts during 1872.

A.R. Chafee took the lead on the relatively small Arthur Ditch, also known as the town ditch. Benjamin Eaton, who would later become Colorado’s governor, partnered with John C. Abbot to build the Larimer County Canal No. 2. The project carried Cache la Poudre water to lands west, south, and southwest of Fort Collins, opening thousands of acres for farming. Compared to earlier efforts, Canal No. 2 was a feat of both engineering and organization, requiring significant labor, money and coordination by its completion in 1893. Eaton and Abbot also installed the Lake Canal that ran north rather than south of the river.

Canal No. 2’s impact was immediate. It allowed farmers beyond the river’s bottomlands to cultivate crops, helped stabilize the colony’s food supply, and gave settlers the confidence that Fort Collins would endure. Eaton’s leadership in irrigation would continue to shape the region: he went on to oversee some of Colorado’s largest canal systems, linking his name permanently with the development of Northern Colorado agriculture.

In tying together town planning, education, and irrigation, the Agricultural Colony era positioned the town as more than a frontier outpost. It became a model of how community, commerce, and water could be woven together in the arid West.

By the mid-1870s, Fort Collins had been transformed. What began as a scattering of homesteads around Camp Collins had become a deliberately planned town with a *platted grid, new institutions, and expanding irrigation. The Agricultural Colony secured Fort Collins’ population base and civic identity. Colorado Agricultural College anchored it as a center for education and agricultural science. Water diversions like Eaton’s Larimer County Canal No. 2 stretched the reach of farming far beyond the riverbanks.

But water remained the valley’s most contested resource. Every new ditch, farm, and household placed more demands on the Cache la Poudre River. The same canals that sustained Fort Collins also put the new town on a collision course with its downstream neighbor Union Colony. In 1874, these tensions erupted into the 1874 Water Wars, a conflict that revealed how deeply life in the Poudre Valley was, and still is, bound to shared water.

Glossary

Crude Ditch: A crude ditch refers to an early irrigation ditch constructed by miners and farmers to divert stream water for their mining and agricultural operations. These ditches were often built without regard for water access rights.

Preemption: Preemption refers to the principle that certain matters which have a national effect are governed by federal laws, rather than any contradictory state or local laws that may exist. This doctrine is based on the U.S. Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, which specifies that federal law preempts inconsistent state law.

Platted: Platting is the process of dividing or combining land into legal lots or parcels. It involves creating an official plat map, which is a detailed survey drawing that defines lot boundaries, public access roads and easements, zoning and land-use restrictions, drainage, flood zones, and infrastructure plans.

Explore

Consider visiting sites in our heritage area like the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, the Avery House, and the Colorado State University Morgan Library Archives and Special Collections!

References

Alfred A. Edwards, 1911. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, Historic Photographs Collection. https://fchc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ph/id/13774/rec/13

Old Fort Collins, 1865. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, John Remington Collection. https://fchc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ph/id/13937/rec/3

New Mercer Ditch and Larimer County Number 2 ditch, 1966. Fort Collins Coloradoan. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, Coloradoan Collection. https://fchc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ph/id/13699/rec/6

“An Agricultural College.” The Colorado Transcript, February 9, 1870. Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection. https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=CTR18700209.2.23&srpos=63&e=–1869—1871–en-20–61-byDA-img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA-agricultural+college——-0——

Old Main, Colorado State University, 1879. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, Historical Collection. https://fchc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ph/id/3086/rec/1

Prospectus of the Fort Collins Agricultural Colony of Colorado. December 9, 1872. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, Museum Artifacts Collection. https://fchc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ma/id/13930/rec/3

Robert A. Cameron and Franklin C. Avery. Map of the Town of Fort Collins, 1873. Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, Historic Maps Collection. https://fchc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/hm/id/220/rec/3

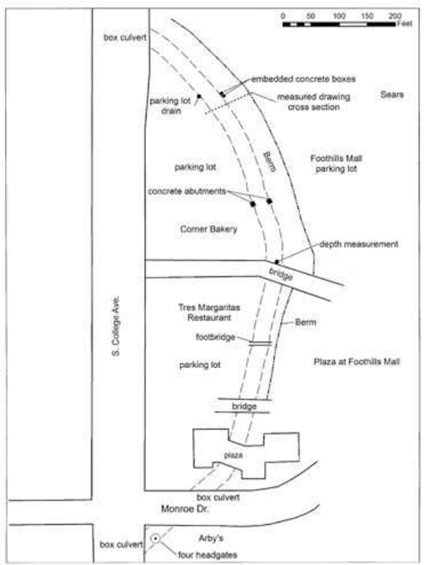

Ron D. Sladek. Larimer County Canal No. 2, Level II Documentation. Tatanka Historical Associates. July 18, 2013. Colorado State University Libraries, Local Water Resource History Collection. https://archives.mountainscholar.org/digital/collection/p17393coll174/id/999

“Early Agricultural Colonies and Cooperative Irrigating.” Colorado State University Public and Environmental History Center. https://pehc.colostate.edu/digital_projects/dp/poudre-river/crops-livestock/agricultural-colonies/

“News Flashbacks: Alfred A. Edwards Tells of Valley as It Was When He Came in 1869.” Fort Collins Express, September 29, 1935, 6B. Fort Collins History Connection. https://history.fcgov.com/newsflashback/edwards

“History of the State Agricultural College – 1895.” Fort Collins Historical Society, July 3, 2018. https://fortcollinshistoricalsociety.org/2018/07/03/history-of-the-state-agricultural-college-1895/

Taku Onozato. “The Foundation of Colorado Agricultural College – Early days of Colorado State University.” October 5, 2015. https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.psu.edu/dist/6/34122/files/2015/09/Colorado-State-University.pdf

Charlene Tresner. “Fort Collins – Its History in a Nutshell.” 1981, updated 2016. Fort Collins History Connection. https://history.fcgov.com/explore/city-history

“A Brief History of Larimer County.” Fort Collins History Connection. https://history.fcgov.com/explore/county-history

Wayne C. Sundberg. Fort Collins at 150: A Sesquicentennial History. San Antonio: HPN Books, 2014.

A History of Fort Collins Water Utilities: From Snowcap to Water Tap. Fort Collins: City of Fort Collins, 2017.

“Where Did All that Water Come From?” Eaton Area Historical Society. https://historicaleatonco.org/where-did-all-that-water-come-from/