Guest Blog by Katherine Mercier, Windsor’s Museum Education Coordinator

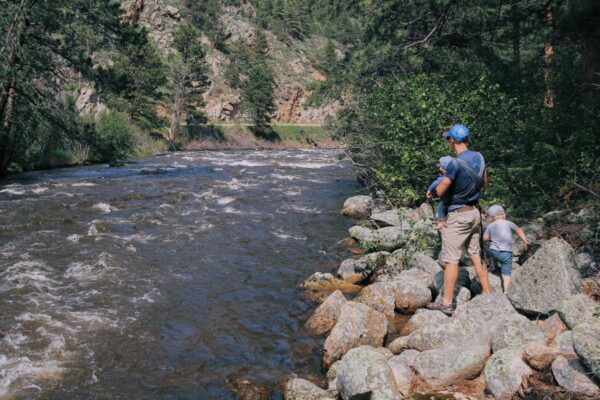

If you have ever been to the Town of Windsor just north of the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area, you have probably noticed water: Windsor Lake, the No 2 Ditch Canal, Chimney Park Pool, the Poudre River that snakes through the southern part of town. Windsor has grown up alongside water, following the Greeley # 2 Canal that was painstakingly dug in the early 1870s to bring much-needed irrigation to dry farm fields. In the 1800s, water meant survival for Windsor, but in the 1960s the role of water began to expand to something else: fun and recreation!

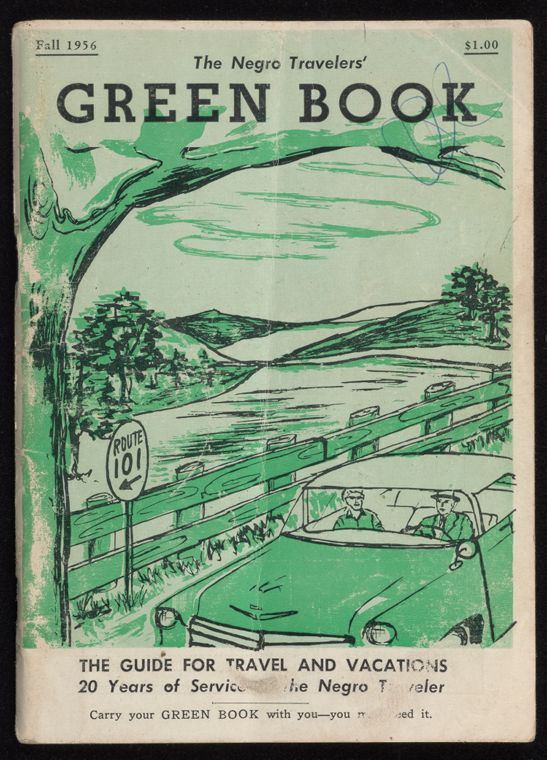

If you were visiting Windsor in July 1964, in addition to the brand-new song “A Hard’s Day Night” by the Beatles, you would have heard discussions about the latest hot button topic in town: should Windsor get a swimming pool? The debate was intense. Some community members were in favor of creating a private, members-only pool funded by citizens. Others wanted a public pool funded by the town. Town leadership eventually decided that Windsor needed a pool that was open to all.

In May 1965, the town parks committee announced exciting news: plans were in place for Windsor’s first town pool! The committee, which consisted of residents Harold Hettinger, Ed Eichorn, Glenn Anderson, Gene Morey, and Bill Kirby, was hoping to lease a plot of land in “Lakeside Park” (now Boardwalk Park) for the pool. In 1966, the committee received a $12,000 federal grant to help fund the pool. Additionally, the community came together to ensure the pool’s success. Town organizations fundraised for the pool; the Boy Scouts had a bake sale, and local businesses hosted a car wash and a hamburger sale. These extra funds enabled mayor Wayne Miller to break ground on the swimming pool on April 20, 1967. Conceptual drawings were published, and construction went quickly.

Conceptual drawing of Windsor’s first swimming pool, April 27, 1967, Windsor Beacon. Notice the pool building at top left and the baby pool on the bottom left.

Windsor pool groundbreaking, April 20, 1967, Windsor Beacon. L-R: Ed Brown, Mrs. Ruben Hergert, Mrs. Helen Casten, Mrs. William Haas, Jr., Cheryl Miller, Glenn Anderson, Mrs. Wayne Lutz, Mrs. Thelma Hemmerle, Rev E.F. Jensen (stooping with the spade), Wayne Lutz, Wayne Miller, and Leland Hull.

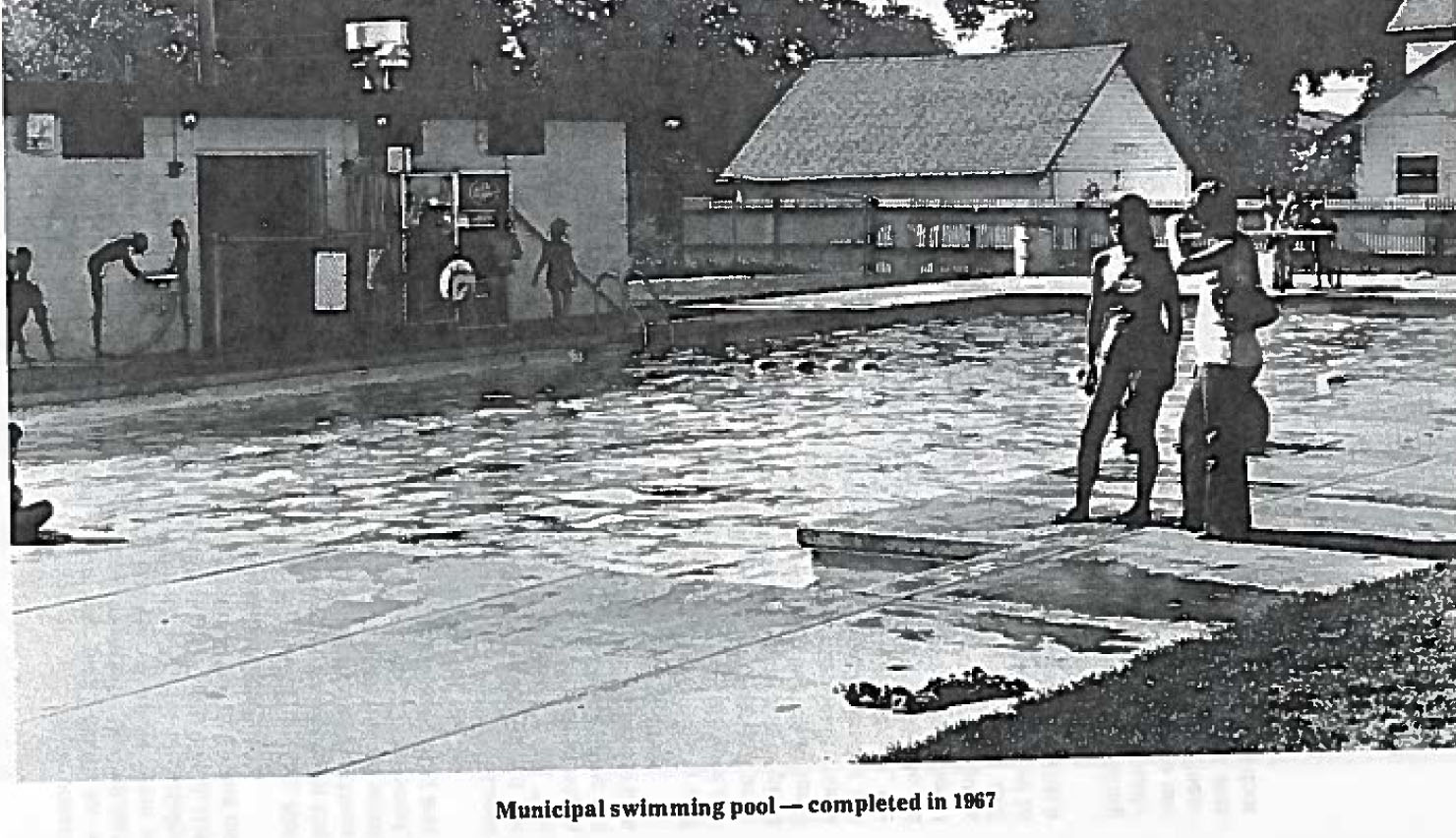

Windsor’s first pool opened in July 1967 to wide acclaim and intense joy from the local children. By 1976, over 3,000 people were using the pool per month in the summer! Considering that Windsor had a population of less than 4,000 people at this time, this shows that the community truly embraced and loved the fun and recreation that this first pool provided.

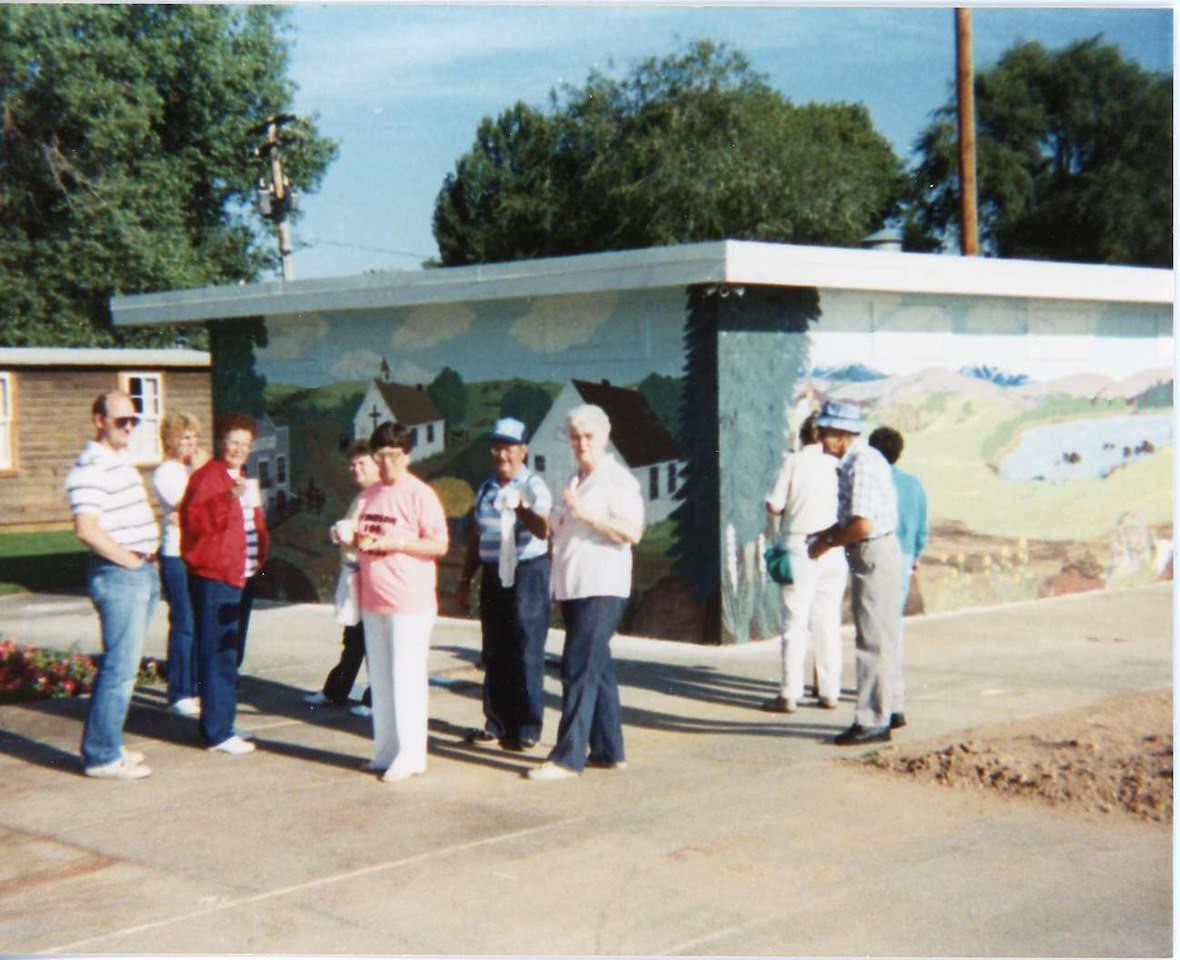

Windsor’s municipal swimming pool in Boardwalk Park, unknown date. Town of Windsor Museums Permanent Collection.

The pool at Boardwalk Park was widely beloved and used for almost three decades. By the mid-1980s, deteriorating conditions at the pool led to the construction of what is now Chimney Park Pool on the east side of town. The municipal pool at Boardwalk Park did not open in 1987 but was used for a popular fishing derby. With the opening of Chimney Park pool in 1988, the old pool fell out of use. By the 1990s, it had been filled in and planted over with grass, and the Windsor Garden Club planted flowers in the old baby pool. On the old pool building, the Windsor-Severance Historical Society painted a large mural depicting scenes from Windsor’s past.

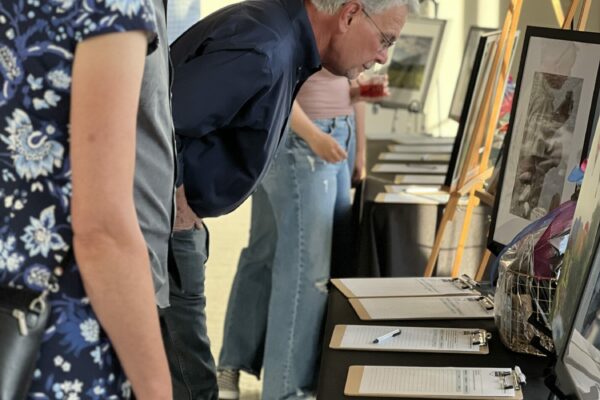

Today, no traces of the pool remain, but if you visit Boardwalk Park, you can see the large, open field where it once was by the Windsor History Museum Farmhouse. In fact, if you attend this year’s Poudre Pour with the Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Area, you will be enjoying drinks and live music right on top of the old pool! The pool may be gone today, but its story is not lost. Windsor’s first pool continues to show us the enduring importance of water in northern Colorado—not just for survival, but also for fun.