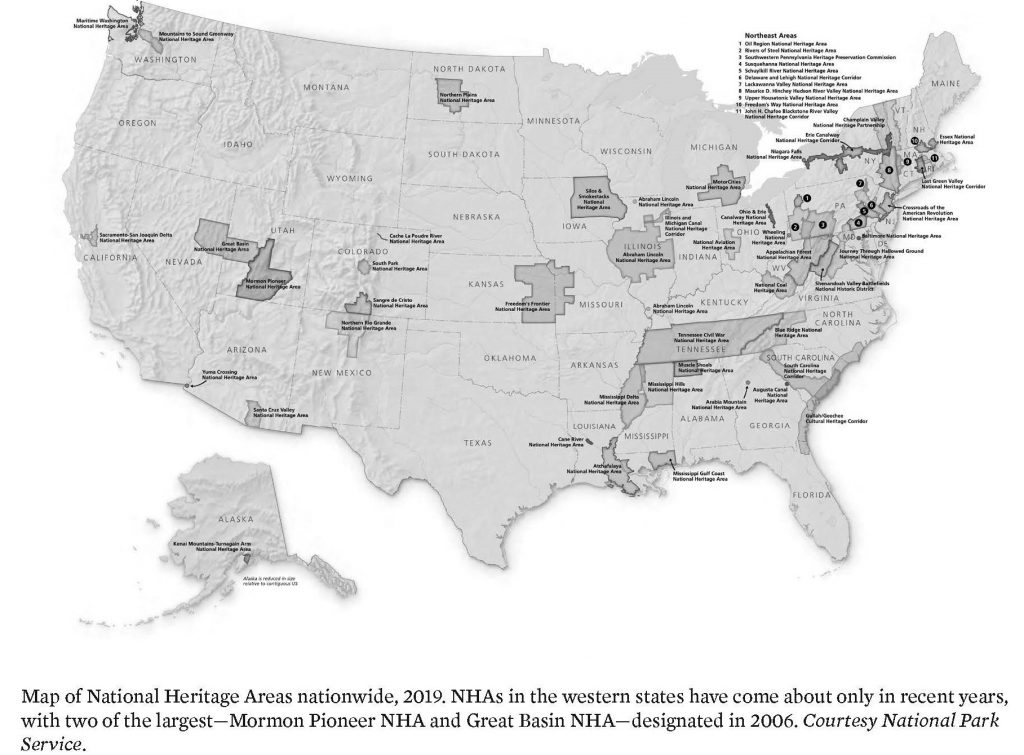

The main answer to this question is WATER! The Poudre River’s water history is not unique in the western U.S. – many western rivers have similar stories about human attempts to survive in arid and semi-arid western river valleys.

What makes the Cache la Poudre River worthy of designation as a National Heritage Area is the manner in which its water history is interwoven into the broader fabric of western water law and technology. The Poudre River’s history, in many ways, is an illustrative microcosm of western settlement that captures the essence of the struggles people faced in living in the dryness that defines the West and, in particular, how they adapted to survive, and thrive, in the dry landscape. And further, the Poudre’s history shows how people continue, to this day, to adapt to new challenges, such as improving the ecological health of the river and providing for recreation on, and in, the river.

As historian David McCullough notes:

History is the story of people.

Water history in the Poudre River valley is no exception. The series of stories that follow explains the role of the people of the Poudre in establishing western water law, water development strategies, new water management technology, and initial recognition of the need to create a sustainable relationship with the limited water environment that exists in much of the West. Again, this need continues today as the population of the Poudre Valley continues to grow rapidly.

The people did not set out to establish new water law, create new technology to manage water, or determine how to divide the limited waters of western rivers. They set out to survive in a dry and harsh climate. As the people of the Poudre adapted to the dry climate, their efforts were innovative enough to be of assistance and use to other western States and many foreign countries.

Organizing and presenting a large sweep of western water history, if even in only one valley, can be daunting if the presentation focuses on each discipline’s (i.e. law, engineering, agriculture, etc.) evolutionary path. The approach used here will chronologically follow the people of the Poudre, explain the water challenges they faced in their day, and describe the manner in which they solved each challenge. The solutions they created for each challenge, when combined over time, will help to explain how we arrived, collectively, at the system of western water management in use today and why there is a National Heritage Area associated with the Poudre River.

Water history in the West is, in very general terms, about subsistence in the 1800s (the frontier was deemed ‘closed’ in 1890), development in the 1900s (the Bureau of Reclamation was created in 1902 and is now managing 180 projects), and sustainability as the 21st Century dawns (as ecosystem health, instream flows and recreational uses are debated, acknowledged, and incorporated into water law). This overarching framework provides a background against which the people of the Poudre lived their lives and confronted water challenges facing each generation.

Read the first story.

References:

‘The Story of People’

National Park Service. 1990. Resource Assessment: Proposed Cache la Poudre River National Heritage Corridor. Prepared by the NPS Rocky Mountain Regional Office at the request of the City of Fort Collins, December [Appendix B of this report is entitled: Historical Context – The History of Water Law and Water Development in the Cache la Poudre River Basin and the Rocky Mountain West] Report can be accessed at: https://archive.org/details/resourceassessme00nati

Information Source: These stories were prepared by Robert C. Ward, a professor and administrator at Colorado State University for 35 years, to assist in training volunteers on the history behind designation of the Poudre River as a National Heritage Area. [In particular, the information permits water history-related sites along the Poudre River to be explained through the lives of people who adapted their use of water to match the semi-arid nature of the landscape.]