By Heidi Fuhrman, Heritage Interpreter

This year we mark the 120th anniversary of the 1904 flood on the Cache la Poudre River, or, as the papers called it, “A Great Calamity.” Read on to discover the story of one river, two days, and thousands of “unfortunate victims of cruel circumstances.”

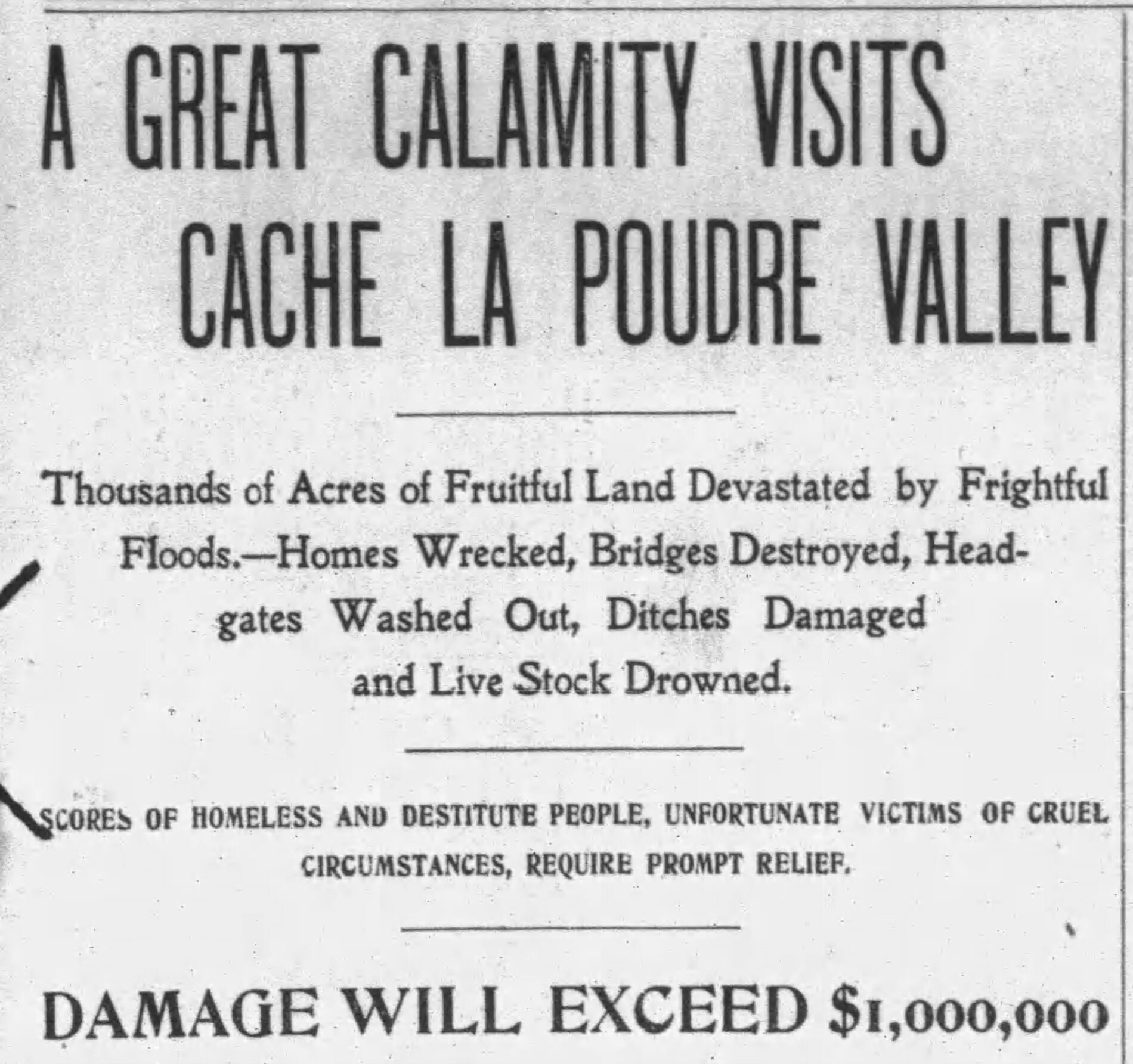

Newspaper clipping from the days following the flood. “A Great Calamity Visits Cache la Poudre Valley. (1904, May 25). The Larimer County Independent, 1.”

May 20th, 1904 began like any other morning along the Cache la Poudre River. Well, perhaps not like any morning—dark storm clouds lay low over the foothills and there were reports that it was raining up-river, and rain in Colorado is unusual—but for the residents of the lower Poudre’s communities the day began like any other.

Down near Laporte Mrs. J.L. Armstrong fed her children breakfast before shooing them out of the house. In Fort Collins, Chris Mason kissed his wife goodbye before strolling over the Poudre to the new dance pavilion he owned on the north bank, pausing to admire the new piano he’d just installed. Down the road, a group of Germans from Russia walked from the immigrant neighborhood to the new Fort Collins Great Western Sugar factory to put in a day’s labor turning beets to sugar.

Further down, at the bend of the Poudre before it wound down through Timnath, Robert Strauss looked out from the cabin he’d built in 1860 on morning light hitting the river. A few miles downriver his neighbor, Will Lamb, told their other neighbor yet again that he couldn’t borrow the hay rake.

In Windsor, William Jones let his flock of chickens and turkeys out before collecting a hundred eggs. And down in Greeley, the farmers near the river bottoms surveyed their fields and were grateful the early onion and cabbage crops were growing well, stretching before turning to finish putting in the last of the beets.

Further up-river, however, all was not normal. High in the Poudre Canyon, and in the tributary streams and canyons that feed the Poudre River, rain was falling. Not just a gentle sprinkle, a deluge. On a landscape that sees an average of fourteen inches of annual precipitation, three to eight inches of rain fell within 24 hours (that’s 20-57% of the annual). The mountain streams and Poudre, already swollen from spring snowmelt, couldn’t contain the water. Unbeknownst to the communities below, Boxelder Creek, a tributary of the Poudre, ordinarily a few feet wide was swiftly growing to a raging river from bluff to bluff, while the Poudre itself was deepening and widening as the North Fork, up in the canyon, dumped its gallons into the already overwhelming torrent.

At about 4 o’clock in the afternoon on May 20, 1904, a wall of water ten to twelve feet high burst through the bottom of the Poudre Canyon a few miles above Laporte, quickly spreading out to more than a mile wide. The Armstrong family, found themselves in the midst of the river, cut off from help by walls of water, scrambling to the top of their home for shelter like the rest of their neighbors in Bellvue and Laporte as the river swept away their buildings, gardens, and bridges. Someone managed to phone Fort Collins before the lines were swept aside, alerting the community that a flood was quickly heading their way.

An hour later, at five o’clock, the flood hit Fort Collins. At four o’clock the river was flowing about 900 cubic feet per second, by six o’clock it was flowing at least 30,000 cubic feet per second (afterwards the USGS commissioner estimated it was closer to 40,000cfs, the yearly average today is around 300cfs). As the water commissioner later wrote in the USGS report, “The flood was down …almost before anyone could remove anything out of the way, and had it been in the night there would probably have been a great loss of life as well as property.”

Luckily for the residents of Fort Collins it wasn’t night, but as the newspaper reported, “…scores of families were driven from their homes in great haste, often compelled to wade through muddy water waist deep to places of safety. Nearly all their belongings, except what they had on their backs at the moment, were left to become the playthings of the rolling, surging flood.” (Larimer County Independent May 25, 1904.)

Rolling and surging it was. Moving houses from their foundations or sweeping away the lighter ones, wiping out gardens and fields, and destroying all but two bridges between the canyon and Greeley. Steel or wood, nothing could stand against the flood water. Chris Mason stood on the north bank near the river—now over a mile wide and running down College Ave five feet deep—with thousands of other residents, watching the “work of destruction” and the dance pavilion, piano and all, collapse and be swept away, taking out the railroad bridge. Across the river his wife, with their children, sought refuge on the second floor of their home, “with fear and trembling,” while through the night a river up to the windowsills swept through the lower level. The next morning their neighbor, Jim Clayton, swam out and rescued them one by one although he refused a final trip to rescue the family chicken.

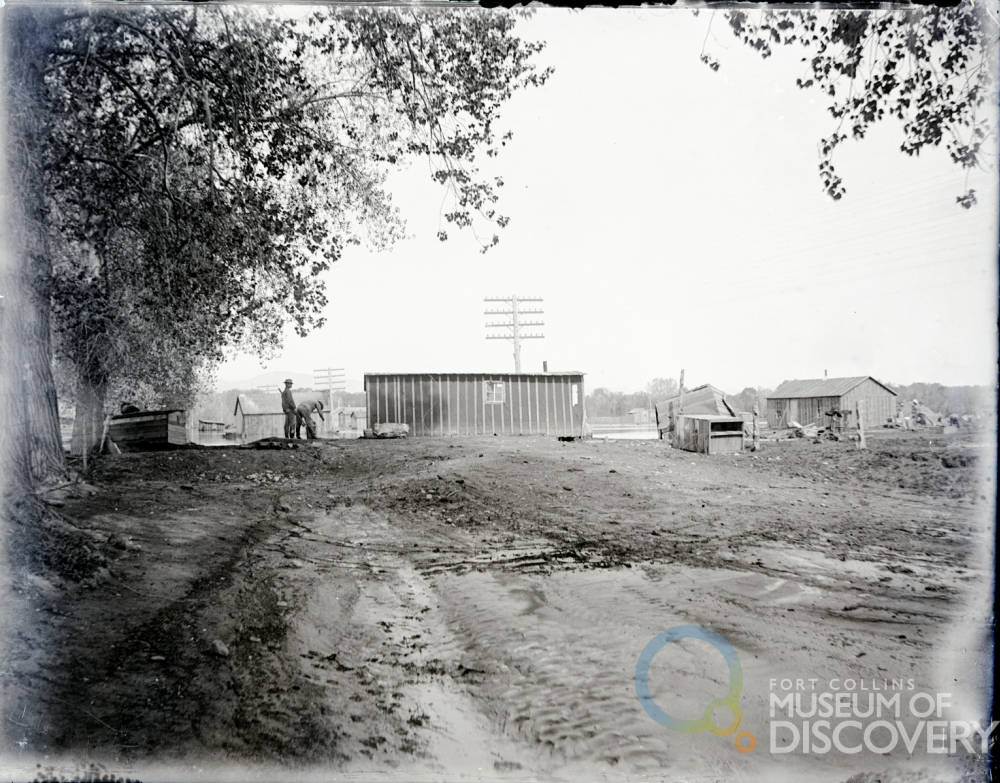

The sugar factory was surrounded by feet of water and the workers found themselves trapped for the night. Thousands of pounds of sugar escaped being ruined by only six inches. Meanwhile, their families, watched as the entire immigrant neighborhood (now the neighborhoods of Buckingham & Andersonville) was swept away.

Flood damage at Buckingham Place which was the Great Western Sugar Factory housing for the German-Russian beet workers located in Lincoln St. between Willow and Lemay. Image Credit: Archive at Fort Collins Museum of Discovery. [H02438]

By seven o’clock the height of the flood swept through Fort Collins (although it would take hours to recede) but was only just reaching the communities downstream …

Read Part 2 for the rest of the stories of Robert Strauss, Will Lamb, William Jones, and the other residents downriver.

References

“Destructive Floods in the United States in 1904”, United States Geological Survey, 1905. p154-156.

“Floods in Colorado,” United States Department of the Interior, 1948. p51-59.

Fort Collins Express, May 25, 1904. (Access on Newspapers.com)

Fort Collins Weekly Courier, May 25, 1904. [Read the full newspaper on the Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection].

Greeley Tribune, May 26, 1904. [Read the full newspaper on the Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection].

Larimer County Independent, May 25, 1904. (Accessed on Newspapers.com)

Windsor Beacon, May 28, 1904. (Accessed on Newspapers.com